After Sikkim became India's 22nd state in 1975, its border with China became the Sino-India border. Forty-two years after the monarchy of the Himalayan kingdom was deposed following a popular referendum, the region remains a matter of international interest writes Global Times.

Sikkim occupies a special geographical position. It lies on the border between the two most populous nations in the world and is close to India's "throat," the Siliguri Corridor. In any regional war it would be a prized target.

Sikkim's past as an independent kingdom is being forgotten by many. But there are many Sikkimese who still don't feel truly Indian.

No Chinese allowed

Chinese find Sikkim a difficult place to visit. Lü Pengfei, who was a correspondent in India for three years, told the Global Times that he heard he could charter a car from Darjeeling into Sikkim while in the town on a reporting trip in 2015. He didn't dare do it.

"When I came back to New Delhi, I sent an application to the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs as well as Sikkim state's office in New Delhi for permission to travel there, but it wasn't granted," he said.

A Nepalese national who has traveled to Sikkim before told the Global Times he has failed to take Chinese friends to the region.

"Chinese and Pakistanis are almost never allowed inside Sikkim. It's not strictly forbidden, but the application process is complicated," he said.

India's Bureau of Immigration website says Sikkim is a "restricted/protected area." According to the website "visa applicants who wish to visit a restricted/protected area are required to fill in an additional form."

According to the Sikkim Tourism bureau's official website, restricted and protected area permits can be obtained from Sikkim Tourism Officers on the strength of a valid Indian Visa and are issued free of cost.

But it was noted in the document that "the nationalities of Pakistan, Bangladesh, China, Myanmar and Nigeria will not be issued a permit without the prior approval of the Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi."

To the east of Sikkim is Bhutan, to the west is Nepal and to the north is China. The region has no railway or airport. The Global Times reporter found that cars and their passengers heading into Sikkim are subject to checks.

Forty-two years after the annexation, Sikkim is clearly still a sensitive area. Many people approached by the Global Times for interviews said they would rather not be quoted on this issue as they fear they might have difficulties traveling to India in the future.

Sandwiched in between

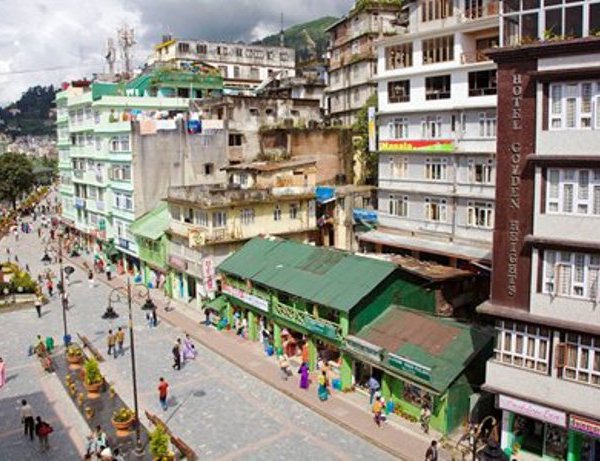

For most visitors, there's nothing tense about Sikkim, a quiet and rapidly-developing tourist spot.

Sikkim's 7,000 square kilometers are home to 600,000 people, the smallest population of any Indian state. According to an article published in the Hindustan Times in March by reporter Sarita Santoshini, Sikkim is India's third-richest region (after Delhi and Chandigarh) by per capita income.

According to the New York Times, "Sikkim has been India's fastest-growing state since 2004, but somehow its growth story has not been in the limelight as much as Gujarat or Bihar, for example. Tucked away in the Himalayas, India's Sikkim state has averaged an annual growth of 12.6 percent over the last eight years."

Santoshini wrote that despite this development, Sikkim's suicide rate was 37.5 per 100,000 people in 2015. That's not only more than triple the Indian average of 10.6 but way above the global average of 11.4. Sikkim's unemployment rate is also India's second highest, more than three times the national average of 5 percent, and the state has a serious drug problem.

The high expectations and vulnerabilities of those born after the state's merger with India in 1975 have resulted in many turning to drugs and suicide, Kunal Kishore, a United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime official, told the Hindustan Times.

Sikkim's chief minister Pawan Chamling was quoted by the Hindustan Times last week as saying "the people of Sikkim did not merge the state with the Indian union to become a sandwich between China and Bengal" in a public function in Namchi, Sikkim. The quote aroused controversy.

He later said that he was misquoted, clarifying that "as far as national security is concerned, the government of India is appropriately handling the matter. We fully support its efforts, which are addressing the national security concerns in the best interest of our country," according to India Today.

Sikkimese identity

On question-and-answer website Quora, under the question "Are Sikkimese happy to be Indians?" one user who claims to be Indian said, "Whether they are presently happy to be Indians, it depends on the individual." Another who identifies himself as a resident of Sikkim, wrote, "Sikkimese are quite happy to be Indians. They can enjoy all facilities throughout India just like other Indians do."

Another user, who goes by the handle Siesta Fiesta, wrote, "As a well-meaning Sikkimese, my unbiased opinion urges me to state that in today's era of a competitive and cooperative evolving global village, as an independent country or a kingdom, Sikkim would have struggled and suffered inadequacy. India saved Sikkim in a big way."

However, he goes on to argue that Indian's annexation of Sikkim still casts a shadow over its people. "The people of Sikkim were gullible, innocent and had no idea where they were casting their votes. They were given a choice between 'democracy' and 'monarchy' and were not smart enough to decipher that democracy equated Union of India ... There is a section of people disgruntled at the merger. When people question my ethnicity or guffaw at my Hindi speaking abilities as I tread mainland India, a part of me also wishes otherwise. A certain amount of identity crisis is definitely faced when ignorant people are not even aware where Sikkim lies," he wrote.

Many Sikkimese prefer to refer to themselves as Sikkimese rather than Indians. Part of the reason for this can be attributed to the Buddhist region's cultural and language difference with the rest of India.

A Nepalese national who traveled to Sikkim three years ago told the Global Times that he felt a sense of kinship in the Sikkim state because Sikkimese are closer in culture to the Nepalese than people in other parts of India. "Both of us are people of the Himalaya. Many Sikkimese have the same family names as Nepalese. Also, 50 percent of Sikkimese speak Nepalese," he told the Global Times.

An article published by Foreign Policy, however, said that in the past few decades, successive waves of immigration from Nepal and India have "reduced the indigenous inhabitants to a minority in their own homeland."

The Nepalese traveler told the Global Times that while he is unable to know what the majority of Sikkimese think of India, from his observation, some of Sikimese do not identify with India. "India adopted a lot of hard-line measures when it annexed Sikkim, and a lot of Sikkimese who now live in Nepal have told me about their anxiety and their discontent over the former Sikkimese monarchy's concessions to India," he said.

But Qian Feng, executive director of the Chinese Association for South Asian Studies, said before Sikkim was annexed, the British Raj had already "penetrated" the region. Sikkim's annexation by India was only a formality, with the locals already acknowledging the governance of India after New Delhi became responsible for the Kingdom's defense, diplomacy and communications after a 1950 treaty.

In an article entitled "40 years on, Sikkim still a divided house over merger with India," Probir Promanik, a correspondent at the Hindustan Times, describes how Sikkimese students were divided on Sikkim's becoming India's 22nd state in 1975. Some celebrated the occasion, while "another section, mostly belonging to Sikkim's ruling aristocracy, called it a 'betrayal' by the 32 political leaders who were signatories to the merger agreement with India," he wrote.

Today, many youngsters in Sikkim have little knowledge of what happened to their state 40 years ago. Many don't even know who the Chogyals, the monarchs of the former kingdom of Sikkim, were. "Was he a king or something? Did he not live at Mintogang (the chief minister's residence)?" A young Sikkimese journalist once asked Promanik.

Promanik says that many Sikkimese officials, most of which were former bureaucrats of the Chogyal monarch, would often tell him in private about how the kingdom was "grabbed" by India when he was working in the region. Many of them were still full of respect for the monarch. Palden Thondup Namgyal, the last Chogyal of Sikkim, died of cancer in New York in 1984. His son Wangchuk Namgyal now lives a reclusive life in Bhutan and Nepal. Some older citizens are concerned about his health and whereabouts.

Jiang Jingkui, director of the Department of Southeast Asian Cultural Studies at Peking University, told the Global Times that currently, there is no independence movement in Sikkim. Although some people overseas are calling for such a movement, Sikkim is too small and dependent on the Indian government to be able to achieve independence.

Global Times

- TANAHU HYDROPOWER PROEJCT: A Significant Achievement

- Apr 15, 2024

- AMBASSADOR HANAN GODAR: Sharing Pain With A Nepali Family

- Mar 30, 2024

- VISIT OF KfW AND EIB TO NEPAL : Mission Matters

- Mar 25, 2024

- NEPAL BRITAIN SOCIETY: Pratima Pande's Leadership

- Mar 24, 2024

- NEPAL ARMY DAY: Time To Recall Glory

- Mar 15, 2024