Authors: Nirmala Maharjan and Bindu Sharma

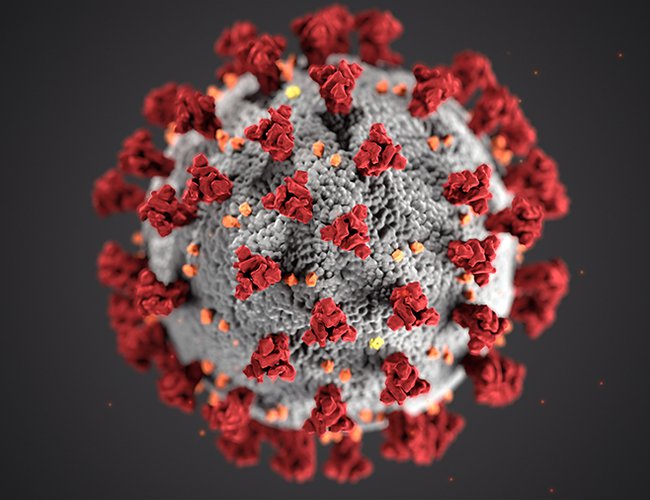

Nepal is expected to face a severe food crisis that might follow long term food insecurity due to COVID 19 pandemic. Humanitarian situations disable pre-existing food safety mechanisms and make households prove to have long term food insecurity. Though the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies claims that the food supplies are sufficiently stored, daily wages workers and people engaged in the informal sectors are walking miles to their villages fearing dying of starvation rather than of the disease.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined this situation as a very serious condition and this statistic mostly includes women and children. In comparison to men, the nutritional needs of women and adolescent girls are less likely to be met in Nepal. Even in a normal situation, women and adolescent girls have less access to nutritious food. Gender discrimination and harmful social norms play a vital role in the nutritional status of females in Nepal. The lower nutritional status has exposed women and girls to greater health risks. According to WHO in 2019, 48 percent of women and adolescent girls of reproductive age suffered from anemia in Nepal. The reason behind was reported to be the lack of essential vitamins and minerals in the body. The nutritional deficiencies are weakening the immune system and exacerbating the cycle of poverty in a woman's life.

The medical doctors and public health experts have recommended eating nutritious food and strengthening the immune system to fight against COVID 19. But women’s situation is getting worse as their prescribed gender roles have taught them that they should live their lives on leftovers of male members and elders of the family. The stereotypical gender responsibilities of women have defined that they should perform their reproductive and household unpaid care work. Traditionally, women are the in-charge of food preparation and serving to family members, yet they are given less priority to themselves in terms of food quality and quantity in comparison to men. The power relations between men and women had created women’s inadequate access and control over food and resources. Nutritional needs of women and girls will further deteriorate as families have less access to food because the lockdown has disrupted the food security system, reduced family income, and people are being left jobless. In this situation, on one hand, females in the family get the least priority for dietary and enough food, and on the other hand their household workload increases and their dietary needs remain unmet due to established gender discriminatory social and cultural notions.

As per the latest update of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, 65% of the total population is dependent on agriculture. However, Nepal has not been able to grow enough food for its population. Women and girls from the major workforce in seed conservation, plantation, cultivation, maintaining farms and harvesting, etc. Currently, it is the season for crop harvest and plantation in Nepal. Practically, the agricultural sector should not be affected by this pandemic but due to lockdown, the seasonal migrants from Nepali families who had migrated for seasonal work to the city, town and India are stuck on the way. The lockdown, labor shortage, restriction on mobility, and restriction on transportation have caused major implications on the agriculture sector. The situation has also invited agricultural responsibility solely in the women's basket. The delay in harvesting may lead to more severe food shortages and high market prices in the near future. Nonetheless, in the long run, women and girls have to directly or indirectly confront a discrepancy for a balanced diet due to food scarcity and gender inequality in food distribution.

The problem of food security is a long-standing issue for Nepal. Time and again we have been facing natural and human-made disasters that have been affecting our food system. Natural disasters like drought, flood, landslides, and scarcity affected a limited number of people. Whereas the massive earthquake and border blockade affected the entire population of the country. Women, girls and marginalized people have been the most vulnerable and hard hit by these disasters and humanitarian crises. COVID 19 is repeating the same situation and worsening the sustenance status of women and girls. Food insecurity and malnutrition are on the rise and further intensified during disasters. Identifying such humanitarian crises, various relief packages are distributed by the government and non-government organizations. The relief process becomes a cumbersome process for women, girls and marginalized groups and the absence of women leadership and participation in designing relief packages have created a huge gap in meeting the women’s and girls' requirements.

The Constitution of Nepal (2015) guarantees the right to food and food sovereignty as a fundamental right. According to the provision, the government should provide food in emergency situations like natural and human-made disasters to its citizens to reduce the implication of food and nutritional insecurity. The federal government should coordinate with the provincial and local governments ensuring regular access to food with adequate nutrition and quality of food without discrimination to all citizens. Similarly, the National Planning Commission has envisioned that Nepal will progress from least developed country to a middle-income country by 2030 in current fifteen five-year periodic plans whereas international convention, sustainable development goal also envisioned No hunger by 2030. In the present condition, Nepal has taken good strategies and plans but it is not enough. The fifteen Five Year Periodic Plan, the nation has taken a strategy for multi-sectoral nutrition in coordination with the local level and improve and promote healthy food behavior to reduce malnutrition through health facility providers. If Nepal wants to ensure food security, the strong coordination between three tiers of government, stakeholders and civil society organization is necessary. Several line ministries like the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development, Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation, Ministry of Health and Population, Ministry of Women, Children and Senior Citizen, and government other bodies need to work together to end the hunger rate and food security ensuring gender equality. A proper institutional mechanism should be kept in place to mitigate and integrate the efforts.

Along with the relief program, to avoid the recurrence of food insecurity and lack of nutrition, women, and girls should be capacitated with awareness, knowledge, and skills to access the resources. In order to improve the economic status of women and girls, they should be engaged in sustainable livelihood options. Nevertheless, Nepal has the best time to integrate the program in the current yearly local level planning process from the bottom-up approach. This might be the right time to formulate gender-responsive and transformative programs ensuring that women and girls are valued in society and they can exercise their fundamental rights where they can claim their freedom of right, voice and choice.

Bindu Sharma is a graduate of international cooperation and sociology. She is active in the field of women’s human rights in Nepal and is majorly interested in issues related to gender, migration and economy.

Nirmala Maharjan: Nirmala Maharjan Gender Equality Diversity and Social Norms Specialist. She has completed her Master in English Literature and Post-Graduation in Women's Studies. She has a keen interest on social norms, gender, social inclusion and governance issues.