In the

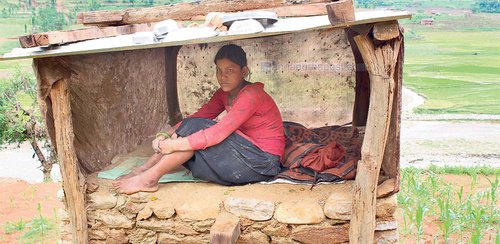

early morning of July 7, an 18-year-old Nepali girl was found dead. During her

menstruation period, according to a Nepali tradition called chhaupadi, she had

been sent to a little hut, where a poisonous snake stung her twice. Separated

from her family, she was unable to get help. The incident was shocking to me.

The next

morning I shared the news with my Nepali friend Ruhy. She didn’t show much of a

shock. “Actually, even now, when I’m at my periods, my dad won’t touch me or

allow me to enter the kitchen. Women are viewed as ‘impure’ and ‘dirty’ during

their periods -- a bit nonsensical, right? But chhaupadi is indeed pretty

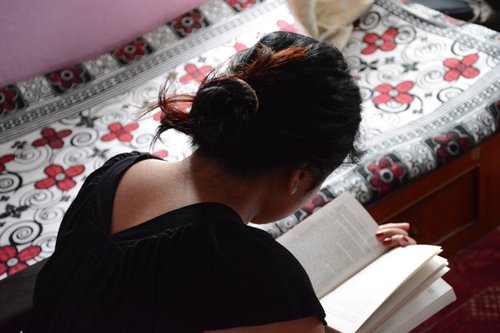

common here,” she commented, shrugging rather sarcastically. Ruhy is my host

sister. Staying at her house for nearly a month, I got a chance to fully

observe and experience local Nepali’s life, or more specifically, a Nepali girl’s

life. Get up at 6; cook breakfast for family; go to school; come back and cook

lunch; wash the clothes or do some farm work; cook dinner; wash the dishes—cook,

clean, cook, clean—the two verbs almost sum up Ruhy’s daily routine. Sometimes

I see men in the house cozily lay on the sofa, watching TV, and I asked why

they didn’t help with the housework. “Hah, that’s the women’s job,” Ruhy’s

uncle answered carelessly, yawned and switched another channel.

Yet it seems to me that here women’s “job” isn’t just to cook and to clean, but also to serve and to obey. In remote areas like far-western Nepal, girl’s marriage is always arranged by her family in order to follow the social norms, like same-caste-marriage, which is why among the countless temples and shrines, there are many, like the Pashupatinath, for women to go and pray for a good husband, but not a single one for men to pray to have a good wife—deprived of the right to make decision herself, she could solely depend on the unknown “fate” or “fortune”. Once I asekd Ruhy’s mother about her opinion about divorce, since her marriage is completely arranged by others and she hadn’t met Ruhy’s father before the wedding. It was just a guess, but she seemed quite confused and unfamiliar when hearing the word. Then she smiled, a bit embarrassed, slowly and firmly shaking her head, “Ehh, no...That’s not possible.” And not surprisingly, the typical Asian feudal idea of a family—son weighs more than daughter—fails to be dispelled in Nepal as well. I recalled that when I visited my Nepali friend Sunni’s home, though he liked to stress how much he was satisfied with his five daughters, he still kept murmuring how much he wished to have a boy.

It is almost my natural inclination to care more about females, and it’s almost my very first reaction to try to excoriate such tradition. Conservative, rigid, unequal—these are words that I first came up with when I thought about the aspects of sex and gender in Nepali culture. However, the longer I’ve been staying here, the harder I find to just criticize—not because I tend to regularize such culture over time, but the culture itself had unfolded a far more complicated and extremely diverse nature, which I could neither simply regularize nor criticize.

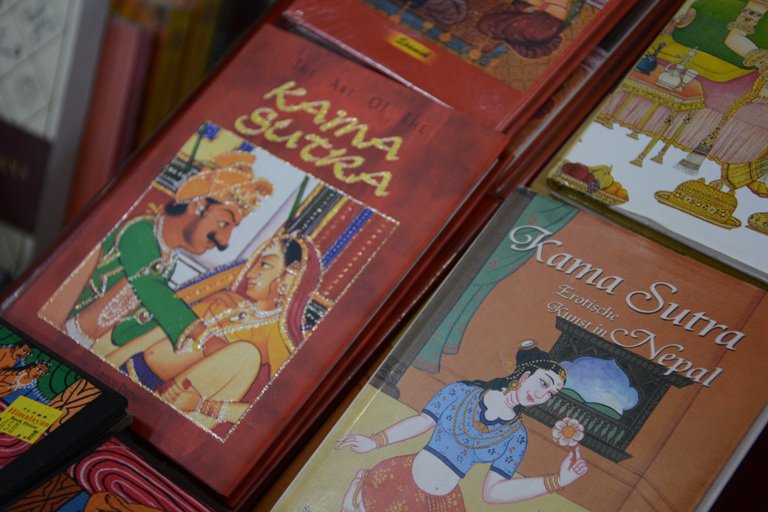

In

Nepali tradition, things related to sex and gender are always something

obscure, even a taboo. Countless norms exist to make women behave “properly”.

In my host family, wearing pants or skirt above knees and getting home later

than 6pm are considered “improper” for women, and I always felt constrained

when walking among them. Yet it is totally different when I take a walk in

Thamel, the most busy and welcome place for tourists, or the red light area of

Kathmandu—the other name that it is famous for. Traditions are exiled here;

instead they come in the open air here, mixed with the desire and a hidden

invitation of sex. Erotic carvings in Durbar Square are made into souvenirs to

attract tourists. Paintings of man having sex with woman in incredibly various

gestures are openly hung in shops. In the evening, sometimes till midnight, I

still can hear the deafening music roaring in thousands of pubs and bars, streets

away, and can sometimes see the tangling bodies dancing in extreme delight from

the window from which the colorful disco lights spill out. Nights here are

never quiet.

Thus, every time, I’m travelling between the local residential district and Thamel, I feel like the bus is taking me from one extreme to the other. I can’t help thinking about Xuan Zang, the first Chinese to land on Nepal, who described this country as “an isolated valley surrounded by endless mountains...there are countless temples here, decorated in precious jewelries...full of monks and pilgrims, people are remarkably religious and devout”(Shi Jia Fang Zhi, translated by me) And thousands of years have passed since, now it is my first time in Nepal. Engulfed by the humid and exotic air, this Chinese girl felt a bit overwhelmed, yet more curious and enchanted to walk deep inside into this city. It is no more isolated; nowadays the country largely depends on tourism and is welcoming travelers from all over the globe every day. There are still a lot of temples, but more and more pubs and massage parlors are being built as well. Catering to tourists, hidden services provided by commercial sex workers like strippers and prostitutes are stealthily developed. It’s been an open secret that some massage parlors in Nepal are in fact brothels—“there are hundreds of massage shops with beautiful Nepali women,” as written on the Nepal Nightlife Guide. What comes with these services is one of the most severe issues in current Nepal: human trafficking, or more specifically—girls/women trafficking. According to the International Labour Organization, around 150,000 to 200,000 Nepali girls and women, mostly illiterate and poor, are trafficked to brothels in India alone each year. Days and nights, among the stacked houses in the crooked narrow streets in Thamel, thousands of dark trades are taking place. People can sense the smell of danger in the dark sky.

The booming tourism, while extraordinarily beneficial for the country’s economics, also brings in new and sheer cultures that stand on the other side of Nepal’s tradition. The country seems to grow far from being completely “religious and devout”(Xuanzang), but generally forms a more complex, diverse and vibrant environment where various extremes encounter and clash. Kathmandu is the city that stands at the very center of all these tensions.

I’ve been wondering how people would live among these tensions that are all trying to tear the others apart, until I was taken by my host sister Ruhy to attend the Guru Purnima, the local Teachers’ Day at her university. It was in fact a students’ carnival in the name of teachers. Boys and girls were dancing the latest Nepali hit songs. In the dance, there were some intimate interactions between the boy and the girl, and when they performed passionately on stage, students hailed jubilantly, while teachers and principals sitting in the front, on the contrary, all blushed a little and somehow shyly turned heads around to avoid eye contact with the dancers.

It was

an unintentional glimpse on the audiences. Yet the difference revealed between

these two groups of people did make me realize that there are changes taking

place in the younger generation, a generation that has a more open and

forthright attitude towards sex and gender. They are people standing amid the

whirl of the vibrant culture shock in the city, and trying to find a balance

between the traditional and the modern through their own experiences. Ruhy is

one of them. She managed to persuade her parents to not urge her to get married

because she’s still pursuing her college study. She’s also working on her

start-up of the homestay business and e-tourism. Ruhy has a boyfriend too.

Although her parents object because her boyfriend is from another caste, she

told me that she and her boyfriend wouldn’t easily compromise since they both

dismiss such rigid social hierarchy. The more I get in touch with Ruhy, the

stronger I feel that even though Kathmandu appears to me as a whole in a bit

mess, the city is slowly moving forward under various forces.

And I remember that morning, the end of our conversation was me casually asking Ruhy a question, “but when you become a mother, you won’t practise the chhaupadi, right?” Ruhy laughed. In a confident and firm voice she said, ("Yeah, for sure") “No, I won't.”

Fan Chen

(Fan Chen, currently pursuing journalism and politics at New York University). She can be reached at cf_phoeniee@hotmail.com

- Kathmandu A City of Candor

- Jul 09, 2017