The world entered 2025 with high hopes, as the United Nations declared it the International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation. The intent was noble: to unite nations in the urgent mission of saving Earth’s vanishing glaciers which sustains billions of people, ecosystems and biodiversity. Yet, as the months unfolds, it becomes painfully clear that this year would be remembered not for preservation, but for the destructive surge in glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs) that have left communities reeling across continents.

Glacial lake outburst floods are sudden, catastrophic releases of water from lakes dammed by glacial ice or debris. As global temperatures rise, glaciers retreat at unprecedented rates, leaving behind unstable lakes. These lakes, often held back by fragile natural dams, are ticking time bombs—awaiting a landslide, avalanche, or heatwave to trigger disaster. The frequency and scale of GLOFs have increased dramatically, transforming them from rare events into a harbinger of disaster of our era.

By midway through 2025, the reality of this new era has become unmistakable. Headlines are dominated by stories of destruction from the Himalayas to the Andes, with scientists and policymakers recognizing that the crisis was unfolding faster than ever anticipated. The first half of the year alone saw multiple high-profile GLOF events, underlining the urgent need for adaptation and international cooperation.

The preservation of glaciers is, at its core, inseparable from the trajectory of global temperatures. Scientific consensus is clear that glaciers can only be preserved if global warming is halted and reversed. However, with current emission trends and insufficient climate action, the prospect of actually reducing global temperatures appears increasingly out of reach—more a mirage than an achievable goal. Even the most optimistic climate scenarios suggest that many glaciers are already committed to melting, regardless of future efforts, unless there is a dramatic and unlikely reversal in global temperature rise.

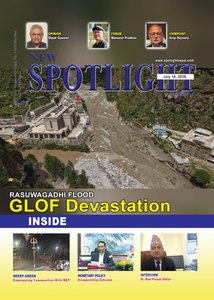

A recent and tragic example of this phenomenon occurred on 8 July 2025 in Nepal’s Rasuwa district. A sudden flood, likely triggered by a glacial lake outburst in Tibet, caused the Bhotekoshi River to surge, sweeping away the vital Nepal-China Friendship Bridge at Rasuwagadhi. The disaster destroyed hydropower infrastructure, left at least 18 people missing and dead —including Nepali and Chinese nationals—and halted cross-border trade. Electric vehicles were washed away, the dry port yard has been destroyed, and rescue operations were severely hampered by adverse weather. Notably, experts found no evidence of extreme rainfall prior to the flood, reinforcing the suspicion that a glacial lake outburst, not monsoon rains, was the reason.

The Rasuwa floods are not an isolated incident. Around the world, GLOFs have left a trail of destruction. In the Himalayan region, often called the “Third Pole,” there has been a fivefold increase in GLOFs since 1950. Over 400 dangerous glacial lakes threaten billions across Nepal, India, Bhutan, and Pakistan. The 2021 Melamchi flood in Nepal and the 2013 Kedarnath flood in India serve as grim reminders of the scale of devastation. In the Andes, countries like Peru and Chile face repeated GLOFs that have wiped out villages and critical infrastructure. Efforts to artificially lower lake levels are ongoing, but new lakes form faster than old ones can be secured. Europe is also not immune, the 2022 Marmolada glacier collapse in Italy, which killed 11 people, highlighted that even smaller European glaciers can trigger deadly avalanches and floods as they destabilize. Meanwhile, Alaska and British Columbia have seen GLOFs damage roads, bridges, and salmon habitats, threatening local economies and Indigenous communities.

While the preservation of glaciers remains crucial, the cruel reality is that even the most ambitious climate action will not save many glaciers in time. Scientific studies indicate that up to half of the world’s 200,000 glaciers could disappear by the end of this century, even if global warming is limited to 1.5°C. This plainprojection underscores the urgent need for adaptation—especially in preparing for and addressing GLOFs induced impacts.

The global and transboundary nature of glacier-related hazards demands coordinated, science-driven action. An International Center for Glaciers (ICG) would serve several vital functions. It could coordinate early warning and disaster response by pooling data and expertise to enhance GLOF prediction, monitoring, and emergency preparedness, particularly in regions where rivers and risks cross national borders. It could foster research and innovation by developing and testing engineering solutions to stabilize glacial lakes, slow glacier melt locally, and preserve unique glacier biodiversity. It could support policy and community adaptation by guiding governments and communities on risk reduction, infrastructure planning, and climate adaptation. Finally, it could preserve cryospheric heritage by acting as a biobank for glacier ice and its unique microbial life, safeguarding knowledge for posterity.

What was meant to be a year of hope for glacier preservation has become a year of analyzing with the harsh realities of GLOFs. By the midpoint of 2025, it is clear that the preservation of glaciers is increasingly appearing as a distant mirage without a drastic global temperature decrease. The Rasuwa floods in Nepal and similar disasters worldwide are glaring warnings that the world must face the dual challenge of saving what glaciers remain and protecting communities from the hazards unleashed by their loss. Establishing an International Center for Glaciers is not just a desirable goal—it is an essential step toward a safer, more resilient future.

Arup Rajouria

is an internationally recognized expert in climate change and natural resources management, with an impressive career at renowned organizations such as the former CEO of NTNC's CEO, UNDP, UN-Habitat, UNEP, and USAID. He obtained an MPA degree from Harvard

- Glaciers Demand: Annapurna’s Lesson

- Jun 05, 2025

- 2024: A Year Of Missed Opportunities- A Call For Transformative Climate Action In 2025

- Dec 31, 2024

- Himalayan Meltdown: Threat Beyond Borders

- May 10, 2024

- Navigating The River of Doubts: The Evolving Dynamics Of India-Nepal Water Relations

- Jan 08, 2024

- A Cry From The Himalayas: Echoes Of Hope And Compromise At COP-28

- Dec 21, 2023