A man named Nagendra knocked on my door early in the morning on the 2nd day of the New Year 2011 at Ganga Hotel in Burtibang, Baglung district. He informed me about an invitation from an unfamiliar person, a school teacher from Chhoregaon Khunga VDC-9. He asked for my cell phone number and then left my hotel room. About 15 or 20 minutes later, I received a call from a man named Kul Bahadur Chhantyal, who had read two of my articles published in Nishibhuji Awaj in the year 2066. He expressed his desire to meet me and show me an iron mine in his village. Since I had some free time before returning to Kathmandu after completing my duties as the superintendent of the TU Bachelor's degree exam in Burtibang center, I agreed to visit his village, which was a five-hour walk from Burtibang bazaar. I enlisted the help of my friend Bhumiraj Paudel, a local campus teacher, and asked him to prepare lunch for two at Hundraphedi. Kul Bahadur had come down from his village to meet us and arranged for our meal at the home of a high school headmaster named Laxmi Pd. Sharma. We reached there within 45 minutes from Burtibang. Since it was a Saturday, everyone was free. We had a meal of dal, bhat, cabbage, and potato curry before heading up to Lukurban Khanigaon.

We traveled for 3 hours along the bank of Lukurban brook, crossing over more than half a dozen suspension bridges and passing a few hamlets. I had a digital camera with me, so we captured some enchanting scenes and sites along the way, including a wild honey hive on a cliff, fountains, and typical houses of the locals. By 3 p.m, we arrived at his home, where we were warmly welcomed by his wife, Pabitra Kumari Chhantyal, the headmistress of Dhiri Lower Secondary School. She served us boiled pumpkin, fried maize, and black tea.

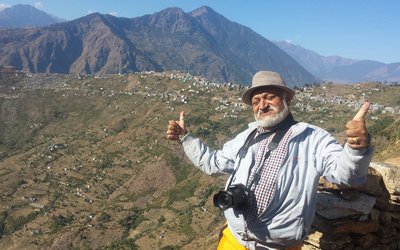

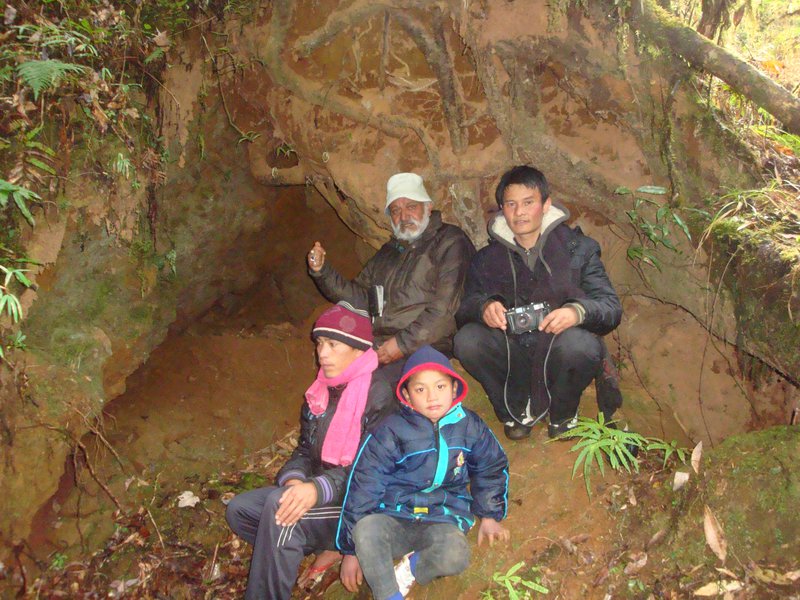

As a grey-haired foreigner wearing a white hat, I was approached by some locals who asked why I was there. My friend explained our mission, and I was introduced to Tilak Pun, a local teacher from Dhiri School, who would accompany us to the iron mining site at the foothill of Durlekdhuri. Despite the heavy rainfall the previous day, the Durlek jungle was covered in snow, making the day very cold. After enjoying some snacks, we continued our journey for another hour, joined by his eight-year-old son, Bibas, through the village of Falamkhani. There, we sought out a blacksmith named Pratiman BK, whose father, Dale Kami, had explored the iron mine in the area. Unfortunately, Pratiman was out collecting firewood, but Mr. Kul Bahadur asked his daughter-in-law to call him back from the jungle to guide us through the iron mine and tunnels.

As we made our way to the destination, it started to rain, turning into snow. We had three umbrellas for the five of us, with me being given one while the others shared the remaining two. We arrived at Kalche Khola (brook) by 5 p.m. and began searching for traces of iron mines, tunnels, and melting furnaces.

The tunnel sites were covered by landslides, burying most of the parts under mud and boulders. However, we found iron ores scattered abundantly on the outer surface of the mine area. Fortunately, Pratiman BK, who used to extract iron from this mine, arrived wearing a cap, a strip muffler turbaned on his head, and a Khasto shawl wrapped around him. After exchanging greetings, we interviewed him with various questions. He shared his past experiences and showed us the sites of the tunnels, ore, and furnace where they used to melt the ore. He also shared a tragic story about his wife and daughter being buried under the mine tunnel in 2033 BS but fortunately rescued. This incident led him to stop excavating iron from the mine.

As dusk approached (around 5:30 p.m.), rain mixed with snow started falling, prompting us to seek shelter inside a bamboo-roofed hut. I delved into his family history, tracing back to his father and forefathers who had migrated from other parts or villages in Myagdi and Baglung districts. My colleague, Bhumi, took notes throughout the conversation.

To my surprise, when I looked up at the bamboo ceiling of the hut, I noticed that it was covered with ganga, raw hazes. I started taking photographs and asked Pratiman what it was. He hesitated and then reluctantly admitted that it was ganga, but seemed afraid to acknowledge it openly. He appeared shocked, as if I were a police officer, and was hesitant to answer my questions truthfully. I reassured him that I would keep the information confidential. My goal of uncovering the truth was nearly accomplished. The owner of the hut was not home as he had moved to awool (down)/bensi for the winter season. Pratiman BK then took us to his home, which had a roof made of Choya and bamboo. We took photos with his family, including his daughter-in-law and about a dozen grandchildren, although one of his sons, a local school teacher, was not present. As night fell, we returned to Kul Bahadur's inn, where we, along with Tika Pun, spent the night. We were fortunate that evening as the locals had slaughtered a goat, so we enjoyed a large mutton feast by the fire. After dinner, we discussed mining, the legend of Chhantyal, stories of the mines, and the occupations of the various groups of people gathered around the fire. Two local shepherd boys, including Kul Bahadur's younger brother Bir Bd. Chhantyal, joined us at the campfire. Even my companion, Bhumi, engaged them in discussions about the country's political issues. I noticed that they all shared a common bond as followers of the communist party.

The following morning, we woke up at 7 a.m. and had tea. The headmistress, Kul Bahadur's wife, had already prepared Aanto, maize porridge, and was ready to cook sisnu (nettle), a wild leafy vegetable, for me as I had requested the day before. However, we thanked her and asked her not to prepare it as we had planned to descend Burtibang as far as possible. We were accompanied by two gentlemen, Tika and Kul Bahadur, as we made our way to the school. At the school, we were shown an iron ball weighing about ten kilos, used as a shot put for sports, extracted from the local mine.

On our way to Burtibang, we were fortunate to meet two blacksmiths, Nandaraj BK and Tekman BK. Nandaraj was heading down to Burtibang to repair his furnace fan, while Tekman was coming up from Burtibang. Bhumi and I asked them many questions and verified the information we had received from Pratiman BK the previous day. The stories and history they shared were consistent. Both blacksmiths were helpful, cooperative, and honest, although they were already drunk early in the morning. Tekman even asked me for money to buy a glass or two of raksi, the local liquor, but I couldn't provide any as we only had a thousand rupees note. Unfortunately, they were out of luck that day. We reached Burtibang bazaar with Nandaraj at 10:30 a.m.

The trek to Lukurban Khanigaon was fascinating, educational, and intriguing for us. There are many other adventurous and informative treks and journeys to explore in the Burtibang area, making it essential for academics and society to continue exploring and learning.

- New ruler: Ruler Failed to Figureout the Ecology of Nepal

- Jul 19, 2025

- Spiritual And Religious Significance Of Tourism In Humla Karnali Region

- Jun 25, 2025

- A Two-Day Trek: Jumla-Rara

- Mar 28, 2025

- Rafting In The Karnali River

- Aug 31, 2024

- Religious Cultural Potentiality of Tourism in Humla

- Aug 18, 2024