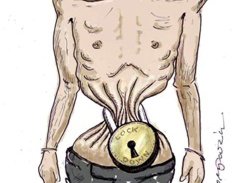

Nowadays the death toll and total cases of Covid-19 transmission each day is shocking everyone. However, very few people are aware that hunger is the biggest cause of death even today. Ten million people die every year (more than 25,000 per day) due to hunger and hunger related diseases. Only eight percent are the victims of hunger caused by high-profile earthquakes, floods, droughts and wars. Over 2.5 million Indians die of hunger every year that counts over 7,000 every day. A child dies from hunger every ten seconds. As per UNICEF report (2018) approximately 3.1 million children die from undernutrition each year. That is nearly half of all deaths in children under the age of five. Thus, the hunger is still the world’s biggest health problem.

As per the FAO report (2019), 820 million people (POU 10.8%) have been suffering from hunger around the world even before the Covid-19. The largest number of undernourished people (more than 500 million) live in Asia, mostly in southern Asian countries. The Global Report on Food Crisis, 2019 revealed that more than 113 million people across 53 countries experienced acute hunger requiring urgent food, nutrition and livelihoods assistance. Globally, 7.3 percent (49.5 million) children under five years of age are wasted, two-thirds of whom live in Asia. WFP estimates (2016) that 66 million schoolchildren go to school hungry. There are, even today, about 40 per cent of the world’s population without access to water and sanitation.

The pandemic is really three crises in one. First, the economic crisis has led to job loss, income loss and a reduction in the global gross domestic product (GDP). Second, a food system crisis has disrupted food supplies and limited the availability of food in markets, especially nutritious foods, while the price of food has also increased. Third, the health crisis and the related lockdowns have led to reduced access to health and nutrition services. So, this triple threathas certainly pushed up the number of undernourished people.It is projected that for any one percentage point slowdown of the global economy, the number of poor-and with it the number of food insecure people-would increase by 2 percent, that is, by 14 million people. The IMF has projected to contract sharply by –4.4 percent in 2020, from 2.8 percent in 2019. That would push around hundred millions of people immediately to food insecure zone.

A preliminary assessment suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic may add between 83 and 132 million people to the total number of undernourished in the world in 2020. However, the global economy is suffering fromprolonged ‘slow down’. So, it is obvious that more people than estimated might have been already pushed to hunger. The WB estimates close to 90 million people expected to fall into extreme deprivation this year. Between present disruptions and future threats to the food supply chain, the pandemic has generated extreme vulnerability in the agriculture sector so as to food security. The economic fallout from the corona pandemic could push even more people into poverty unless urgent action is taken, calling on world leaders to agree an ‘Economic Rescue Package for all’ to keep poor countries and poor communities afloat. According to UN estimates, more than half a billion children worldwide have lost their access to education as a result of coronavirus lockdowns.

Many won’t return to the classrooms after the pandemic, with girls more likely than boys to drop out.The WFP estimates that more than 320 million primary schoolchildren in 120 countries are now missing out on school meals. A recent estimates revealed that by 2022 this nutrition crisis could result in an additional 9.3 million wasted and 2.6 million stunted children. The pandemic will affect maternal nutrition as well, with 2.1 million additional maternal anemia cases, and 2.1 million children born to mothers with a low body-mass index, putting these children at a disadvantage from the very start.

The supply chain disruptions halting the food supply further compound the severity of the pandemic. The latest dire assessment reflects the full or partial lockdown measures affecting almost 2.7 billion workers – four in five of the world’s workforce. Losing job is further losing affordability for thefood stuffs.The cost of a healthy diet exceeds the international poverty line, making it unaffordable for the poor: around 57 percent or more of the population cannot afford a healthy diet throughout sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia. The latest ILO data on the labour market impact of the COVID-19 pandemic reveals a 10.5 per cent drop in working hour, equivalent to 305 million full-time jobs (assuming a 48-hour working week) in the second quarter of the year due to the prolongation and extension of lockdown measures. There is the devastating effect on workers in the informal economy and on hundreds of millions of enterprises worldwide. Among the most vulnerable in the labour market, almost 1.6 billion informal economy workers (out of a worldwide total of two billion and a global workforce of 3.3 billion) have suffered massive damage to their capacity to earn a living. Moreover, Automation, in tandem with the COVID-19 recession, is creating a “double-disruption” scenario for workers. The workforce is automating faster than expected, displacing 85 million jobs in the next five years. Massive job loss will also hard-hit to the labour-sending countries since there would be heavy fall in remittances

Remittance dependent household will lose the coping strategy for hunger. The Covid-19pandemic is hitting hard an already weak and fragile world economy. However, it does not exempt the developed ones as well since casesare more prevalence in those countries. Thus, the pandemic has firsthand impact on availability and access of food stuff around the globe. The consequences of this crisis is particularly severe on vulnerable groups, especially to women and young adults, and those working in the informal sector who have no access to social protection and unemployment insurance. It has hard-hit even harder to the hardcore poor like daily wage-earner, slum-dwellers, disables, refugees and migrant workers. The expansion of the “gig economy” will further increase youth vulnerabilities in employment. Nevertheless, there are some protracted conflicts also going on simultaneously such as; Afghanistan, Yemen, Ethiopia, Burkina Faso, Libya, Iran, Israel, and the Persian Gulf. Millions are on the brink of starvation due to the conflict. Some 74 million people, more than two thirds, of those facing acute hunger are affected by conflict or insecurity. WFP has recently announced a public appeal for donation to feed as many as 14 million Yemenis. One and half billion people still live in fragile who are about twice as likely to be malnourished or to die during infancy compared to people in other developing countries. The Covid-19 pandemic has certainly deepened the severity in those countries. There is also the chance of emergence of new conflicts and/or famine due to this tremor.

Immune system is built with the food intake to deal with the externalities in human body. The fact is that the human races or genes have evolved in course of human civilization and grown up with the herbivorous food around their shelter that made immense immune to disease. But the neoliberal economic policy damaged the local food system and made ubiquitous food that loses immunity. As a result, whatever the disease, the disease can be worldwide. Recent experience has shown that, in countries with less liberal economy, such capacity is not lost immensely. Rob Wallace tracks the ways influenza and other pathogens emerge from an agriculture controlled by multinational corporations in his book “Big Farms Make Big Flu”. Highly capitalized agriculture may be farming pathogens as much as chickens or corn. He writes, “it pays to produce a pathogen that could kill a billion people.” Likewise, Laura Spinney, a science journalist, describes how the big companies pushed out the small farmers closer to viruses that infect them lurk. Starting in the 1990s, as part of its economic transformation, China ramped up its food production systems to industrial scale. With this smallholding farmers were undercut and pushed out of the livestock industry. Searching for a new way to earn a living, some of them turned to farming “wild” species- closer to uncultivable zones-the edge of the forest where bats and the viruses infect them lurk. hence, so did the risk of a spillover. It has contributed to the increasing number of zoonoses. In this way neoliberalism promoted the big firms which not only make big flues but also damage the human immune system. In fact, this is a kind of “neoliberal atrocity”.

The impact on food security generates multiple chain effects in families, society, state and globe as a whole. To some extent it becomes viciously generational. Economic turbulence continued to erode livelihoods and destroy lives. Low- and middle-income countries are exposed to external vulnerabilities. So, the impact goes long-lasting cyclically creating brake on economic recovery even after the viral pandemic is over. Economic shocks are the primary driver of acute hunger. It is forecasted that the global economy as well as per capita incomes would shrink–pushing millions into extreme poverty. The latest analysis warns that COVID-19 has pushed an additional 88 million people into extreme poverty this year– in a worst-case scenario, the figure could be as high as 115 million. The World Bank Group forecasts that the largest share of the “new poor” will be in South Asia, with Sub-Saharan Africa close behind. Therefore, this is much more than a health crisis. It is a human crisis. Nevertheless, the state and the society have to respond these issues, protecting people from Covid-19 and hunger, in an appropriate way. There should be immediate humanitarian response since the people facing acute hunger are in the most dangerous zone. Several nation-states have announced relief package for such vulnerable groups. Some effective measures can be community food banks, food aid, cash or kind transfer, food vouchers, ration-cards, etc. The most challenging issue is the access of food due to the halt in distribution chain and price volatility. For this state has to be proactive to strengthen its regulatory and operational mechanism. Revival of household income will usher the global economy back to life. To keep the employment somehow intact, the ILO assessment report calls for urgent, large-scale and coordinated measures across three pillars: protecting workers in the workplace, stimulating the economy and employment, and supporting jobs and incomes as the Covid-19 outbreaks continues .

These measures include extending social protection, supporting employment retention and financial and tax relief, including for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises. Protective measures are essential to address the economic shock of the pandemic that stimulates vulnerable people to grow up for the economic revival. Countries must commit to do their utmost to protect the labour force, including workers who depend entirely on daily earnings and those in the informal sector and support their employment and income. Direct support to enterprises, particularly to SMEs and mobilize large injections of concessional finance even from the private lending agencies may support to ensure livelihood security. These need to be complemented with coordinated monetary and financial policy measures. In the changed context, diversification of livelihood strategy has to be undertaken that is adoptive with the gig economy. Reducing food loss and wastage can be instrumental to feed the people facing acute hunger. Food wastage occurs in different stages of ‘farm to flush’ process. The most often quoted estimate is that ‘as much as half of all food grown’ is lost or wasted before and after it reaches to consumer. It would preserve enough food to feed 2 billion people- more than twice the number of undernourished people across the globe. It would also increase household income, improve food availability, reduce food imports and improve the balance of trade. However, for that it needs to restore the distribution chain intact, otherwise, the lockdown may further increase the food wastage as the farmers being not able to bring production to the market. Safety-nets are important safe-guards for food security. Civic actions are the crucial safety-nets that build capacity to break through the glass ceiling and bring the emancipatory shift. Likewise, an energetic press may be the best early warning system for famine that country can devise as watchdog.

Foremost concern is to reset the economy with a new dimension. The global production, trade, governance and power structure under corporate regime in neoliberal economy have not been able to eliminate hunger, rather it upheld and reinforced inequalities. The Committee on World Food Security, an intergovernmental body to serve as a forum in the United Nations System, has insisted country-led processes towards the elimination of hunger.The Zero Hunger Challenge, an international commitment envisioned for “world without hunger”, has reemphasized ending hunger by 2025 sustainably. Likewise, the United Nation’s SDGs call on all countries to end hunger in all its forms by 2030.But the present pandemic made it harder to achieve these goals in accredited time.

Countries need a rebalancing of agricultural policies and incentives towards more nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive investment and policy actions all along the food supply chain to reduce food losses and enhance efficiencies at all stages. The research estimates an additional $1.2bn in nutrition funding is needed per year for the next three years, over and above the Investment Framework for Nutrition 2017 estimate of $7bn needed annually to achieve the World Health Assembly 2025 nutrition targets. However, the continuation of neoliberal economic policy is not supportive to achieve this target. It needs protective intervention from the state which focuses on building local food regime-peasants command over food system- that La Via Campesina, the peasants’ movement, has been campaigning since 1996. It strengthens the community resilience on food security and also reduces carbon emission. However, land reform, assuring cultivable land to farmers,and agrarian reform, focusing on value chain, are must in such interventions. The community financing, i.e. community-owned micro banking, would be the essential part for accessing capital to the farmers.

Such economic policy has been termed as ‘Protective Liberalism’ or politically as ‘Liberal Socialism. Inclusive society from bottom to top is the basic part of protective liberalism whereas building inclusive governance from the bottom is the hardcore strategy of the liberal socialism. It would bring the emancipatory shift in the lives of the marginalized ones, i.e. transformative democracy. Food is not only the commodity rather it is a human capability and righteous movement; i.e. right to food and food sovereignty. So, it has been essential to restructure the world economy that favors restoring the local food regime which regenerates the human immune system, protects the environment, respects cultural diversity and rewards human pluralism. The ‘Coronomics’ can be the foundation for Human Economics which would be the ground rule to build the local food regime- homegrown approach to eradicate hunger.

(Dr. Bk, former Secretary for Nepal Government, was a Fulbright Research Scholar at Brandeis University, the USA for 2016/17, is the author of the book "Eradicating Hunger: Rebuilding Food Regime", visiting professor for BF Program of Tribhuvan University/Nepal and the Advisory Editorial Board Member for the International Journal of Commerce and Management Studies, India)

- Protective Liberalism: An Alternative to Neoliberalism, A Warming Agenda For WSF 2024

- Feb 13, 2024

- Caste-based Practices Decreased But Not Momentum: A Review Of The Studies Commissioned By FCD

- Mar 18, 2022

- The Luxury Lockdown: Tackle To Covid-19, Fatal To Hunger

- May 21, 2020

- Rise Of Liberal Socialism To Reshape The Coronomics

- May 07, 2020

- Escalating World Hunger With The COVID-19 Pandemic

- Apr 12, 2020