The Fluid Cartography of Conflict

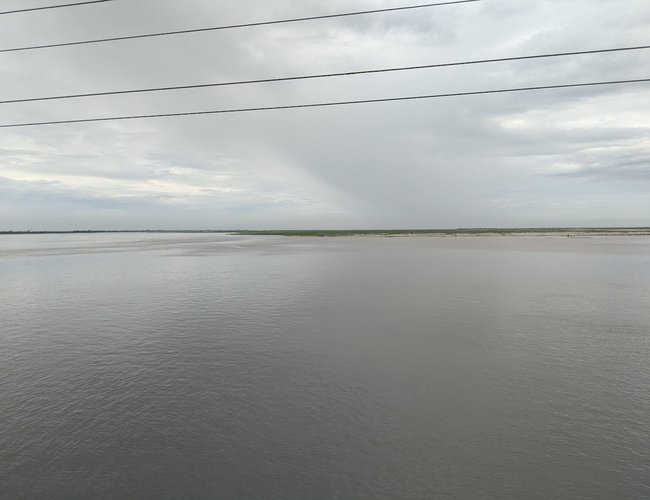

Rivers in South Asia do not merely flow—they speak. They carry the whispers of drowned cities, the echoes of ancient prayers, and the weight of modern betrayals. On a sweltering April morning in 2025, India’s suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty sent shockwaves across the subcontinent. The decision, framed as a geopolitical gambit, reduced a 4,000-year-old lifeline into a bargaining chip. But rivers are more than water; they are living archives. To dam them is to erase history. To weaponise them is to sever memory.

This is not a story of borders, but of confluences. Through seven literary works—each a tributary feeding into the same urgent truth—we chart a path from conflict to kinship. These narratives remind us that rivers do not recognise flags. They carve their own maps.

Empires of the Indus: The Story of a River by Alice Albinia

Imagine a river that birthed cities. Alice Albinia’s journey upstream—from the Indus Delta’s salt-stained shores to Tibet’s glacial womb—is a pilgrimage through time. She walks where the Harappans traded lapis lazuli, sits with Sufi mystics who sing to the river’s soul, and confronts the concrete monoliths of modern dams. “The Indus,” she writes, “is dammed, diverted, yet defiant.”

Albinia’s greatest revelation lies not in the river’s might, but in its quiet alliances. In Sindh, Hindu fisherfolk recount legends of Jhulelal, the river deity revered across faiths. In Gilgit, Kalash elders trace their ancestry to Alexander’s soldiers, their rituals a mosaic of Greek and Buddhist echoes. The Indus, Albinia argues, is a palimpsest of coexistence—a truth drowned out by the cacophony of nationalism.

Rivers Divided: Indus Basin Waters in the Making of India and Pakistan by Daniel Haines

The 1960 Indus Waters Treaty was never about water. Daniel Haines lays bare the Cold War calculus: a deal brokered by the World Bank to stabilise two fledgling nations, not to honour a river’s logic. “They divided the waters,” Haines writes, “but entwined the traumas.”

In Punjab’s borderlands, where the Sutlej and Ravi snake between barbed wire, farmers whisper of a time when canals knew no flags. Haines juxtaposes this with Bengal’s chars—shifting river islands where Hindu and Muslim refugees squat on silt, their identities as fluid as the Brahmaputra. The treaty’s fatal flaw? It treated rivers as property, not as lifeblood.

A River Called Titash by Adwaita Mallabarman

The Titash River dies quietly in Mallabarman’s haunting elegy. Once, its currents cradled the Malo community—Hindu and Muslim fisherfolk who shared songs, nets, and monsoon feasts. Then came the engineers. Dams choked the Titash; concrete replaced rituals. The widow Basanti, her voice cracked with grief, sings to a vanished river: “Where have you hidden your fish, your silt, your mercy?”

Mallabarman’s prose aches with what scholar Subhadeep Ray calls “ecological grief as political resistance.” The Titash’s fate mirrors the Indus’s present: a warning that rivers cannot survive when reduced to irrigation lines on a bureaucrat’s chart.

Chemmeen by Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai

In Kerala’s backwaters, the sea is both deity and destroyer. Thakazhi’s Chemmeen spins a tale as old as the tides: Karuthamma, a fisherman’s daughter, dares to love Pareekutty, a Muslim trader. The Sea Goddess Kadalamma punishes this transgression—or so the lore goes.

But this is no simple tragedy. The novel’s true tension lies in its “mythic ecology,” where human folly collides with nature’s wrath. When Karuthamma’s husband drowns, is it divine retribution—or the cost of overfishing waters stripped of their sanctity? The Indus, too, exacts a price. In 2022, Pakistan’s catastrophic floods displaced 33 million—a reckoning for those who forgot that rivers demand reverence.

Slowly Down the Ganges by Eric Newby

Eric Newby’s 1963 voyage down the Ganges is a comedy of errors—a bumbling Brit and his long-suffering wife, Wanda, capsizing their way from Hardwar to Calcutta. Yet beneath the slapstick lies a prescient satire. Newby mocks colonial hubris (his boat runs aground 63 times) but documents with aching clarity the rituals he witnesses: pilgrims releasing clay lamps at Varanasi, Dalit boatmen chanting forgotten ballads.

“Hydro-orientalism?” Perhaps. But when Wanda snaps, “Must we drown for your poetry?” she unknowingly channels the rage of climate refugees today. Newby’s farce holds a mirror to our folly: we romanticise rivers even as we strangle them.

Is a River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane

Robert Macfarlane’s question is incendiary: What if rivers had rights? In 2025, as India’s Yamuna chokes on industrial foam, Macfarlane joins activists fighting to grant it legal personhood—a campaign echoing New Zealand’s Whanganui River settlement. He walks Delhi’s bone-dry floodplains, where children play cricket on cracked mud, and cites Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things: “The river was alive now. Not just a thing to be used.”

His manifesto is simple: Daylight the buried rivers. Unearth the streams paved over by megacities. Let them breathe. Let them testify.

Toward a Hydro-Poetics of Peace

These seven narratives converge like monsoon rains:

- Rivers as Living Archives: Albinia and Mallabarman show that to know a river is to know who we were—and who we could be.

- Hydro-Diplomacy Reimagined: Haines and Macfarlane demand treaties that honor a river’s agency, not just its utility.

- Eco-Cultural Revival: Thakazhi and Newby remind us that folklore is not nostalgia—it’s survival.

The Indus Waters Treaty suspension is a crisis, but also an invitation. Imagine leaders from Delhi and Islamabad sitting not in air-conditioned halls, but on the Indus’s banks. Let them read these books. Let them hear the river’s stories—of Silk Road caravans, Partition’s bloodied waters, and the fisher girl who still sings to the moon.

As Subhadeep Ray writes in River Fiction of India, “To dam a river is to silence a chorus of histories; to free it is to sing anew.” The choice is ours: Will we be remembered as the generation that weaponised water—or the one that learned to listen?

*Zakir Kibria is a writer and nicotine fugitive. Entrepreneur | Policy Analyst | Chronicler of Entropy | Cognitive Dissident. “Empires decay. Pragmatism

survives. Stay sarcastic.” Email: zk@krishikaaj.com

References

- Empires of the Indus: Alice Albinia

- Rivers Divided: Daniel Haines

- A River Called Titash: Adwaita Mallabarman

- Chemmeen: Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai

- Is a River Alive?: Robert Macfarlane

- River Fiction of India: Subhadeep Ray (ed.)

- Slowly Down the Ganges: Eric Newby

“A river is water, but it is also time—shaped by memory, flowing toward hope.”

- The Tehran Gambit: How America’s War on Iran Accelerated the Birth of a Post-Western World

- Aug 05, 2025

- The Digital Strip Search: How America’s Social Media Visa Edicts Redraw Colonial Borders in Cyberspace

- Jul 14, 2025

- The Iron Silk Road: How a Train to Tehran is Rewriting The World’s Map – And Why The Old Powers Are Terrified

- Jun 25, 2025

- The Kuala Lumpur Pivot: How A Silent Summit In Malaysia Is Rewriting The Global Economic Map

- Jun 16, 2025

- The Rise of Mediation Diplomacy – How Hong Kong’s IOMed Charts a New Path for a Multipolar World

- May 28, 2025