Background

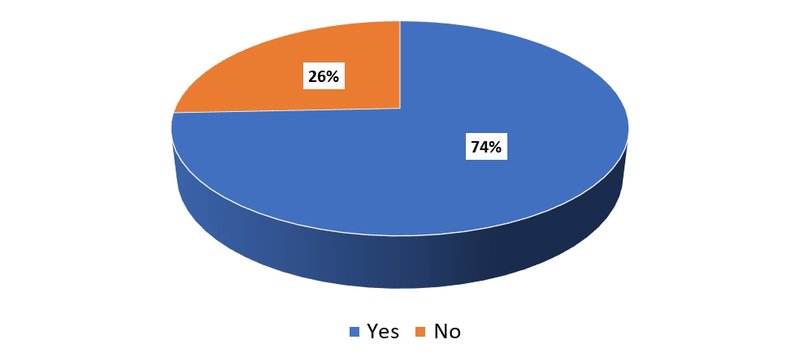

Springs are the main source of water for millions of people in the mountains of the Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH). They are critical to terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. But springs are drying up rapidly, threatening human survival throughout the HKH region. The drying up of springs has adversely impacted local communities, especially women, who are mostly responsible for collecting water for the household. A recent countrywide study by Nepal Water Conservation Foundation (NWCF) and the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) found that springs are drying up in 74 percent of the 300 municipalities and rural municipalities it looked into. In some places, the shortage of water has forced people to migrate from their birthplace.

Despite the urgency, this water-induced disaster has received little attention. Far from trying to solve the problem, local governments have been promoting water-lifting projects that harm the environment and cause springs to dry up. The so-called development model that prioritizes careless, haphazard infrastructure extension has aggravated the problem.

Current situation

Over 10 million people in both rural, peri-urban and urban settlements of Nepal depend on spring sources to meet their water needs. Many springs of the Churia (Siwalik), middle hills and mountains are drying up or have already dried. Studies show that the problem is becoming more severe throughout the HKH. Consequently, communities are facing unprecedented water shortages. People have only two options: either to migrate or find alternative sources of water. Both options are expensive and merely shift the water stress from one place to another.

The recent NWCF and ICIMOD study was built around a survey conducted in 300 municipalities in Nepal and covered the Churia, mid-hills and mountains region. Respondents included top-level officials – mostly mayors/chairpersons, some deputy mayors/vice-chairpersons, and chief administrative officers.

While springs have dried in 74 percent of the municipalities studied(Figure 1), in about 58 percent of the study area, springs have shifted from one site to another – a phenomenon caused primarily by the 2015 earthquake, according to local informants.

Figure 1: Only 26% of the municipalities involved in the study reported no loss or drying up of springs

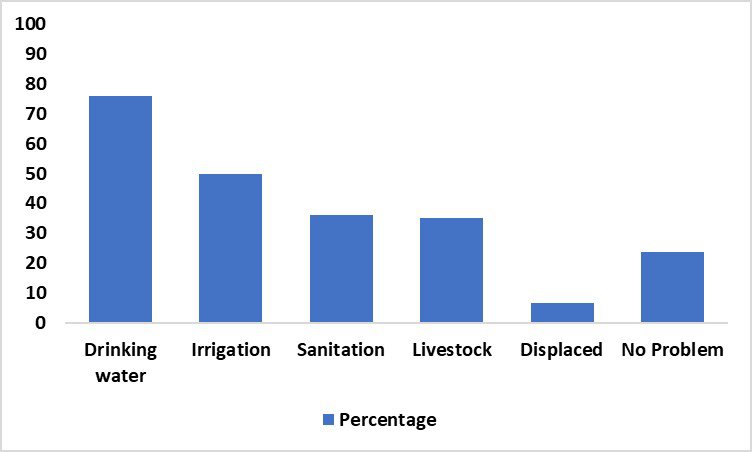

People across Nepal – from the Ilam district in the east to Darchulain in the west –are facing severe water scarcity. Local government representatives from the municipalities studied suggest the drying of springs has different levels of impact on different sectors: 76 percent on drinking water, 36 percent on sanitation and hygiene, 35 percent on livestock feeding, and 50 percent on irrigation and other domestic uses (Figure 2).

Figure 2:Problems caused by drying up of springs

In extreme cases of water shortage, people had no choice but to leave their ancestral villages. According to an article in the Himalayan Times, about 7 percent of the municipalities covered by the study faced such incidents. Some villages of Ram Prasad Rai Rural Municipality (RM) of Bhojpur, Sahidbhumi RM and Mahalaxmi Municipality of Dhankuta, Dalome RM of Mustang and Chhatreshowri RM of Salyan were displaced due to lack of water sources.

Why springs are drying up

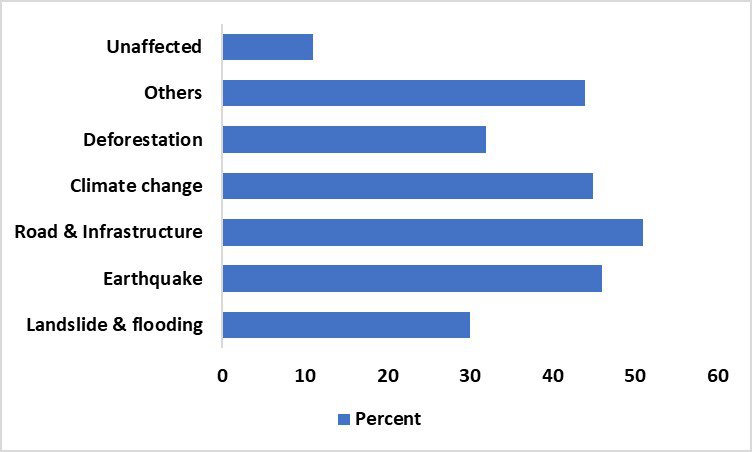

The drying up of springs can be attributed to three major factors – anthropogenic activities, climate change, and seismic events (see Figure 3).

Anthropogenic activities include infrastructure development such as the construction of roads, hydropower tunnels, and cemented irrigation canals; and land-use changes such as deforestation and over-exploitation of natural resources. Unplanned urbanization and population growth, which leads to higher consumption and dependency on springs and other water sources, is also causing water scarcity.

Figure 3: Causes of drying up of springs

In Nepal, infrastructure projects are often carried out without a rigorous environmental assessment, which leads to the depletion of water sources. Local government leaders cited haphazard road and infrastructure construction as the major cause of drying springs (51%) followed by earthquakes (46%), climate change (45%), deforestation (32%), landslide (30%), and other causes like hydropower tunnels, forest fires, destruction of old ponds and aahals (wallows), and concretization of traditional irrigation channels. An alarming finding from the survey is that only 11 percent of the springs are intact and unaffected.

The natural causes are associated with global warming and climate change. Erratic rainfalls have caused the drying of both surface water and groundwater. Rainfalls of high intensity and short duration have intensified water-induced hazards like floods and landslides, causing springs to disappear. Locals say they have not experienced jhari (rainfall of low intensity and long duration) in recent decades. In addition, Nepal lies in a seismically active region and experiences earthquakes of various magnitudes. These earthquakes disturb underground aquifers and alter the direction of groundwater flows, causing springs to dry up.

Another reason why springs are drying is that wallows and ponds that were traditionally used to provide water to livestock and as wallowing grounds for livestock are no longer maintained and have fallen into disuse. These ponds, which with rainwater during the monsoon, were an integral part of agrarian life in the past, not only provided water for animals and plants but also helped recharge aquifers. Although locals still build and manage these ponds using knowledge passed down through generations in some places, traditional customs are increasingly being abandoned, and new wallows are no longer being dug.

Old and sacred rituals associated with water bodies have been disappearing as well. They include festivals like Sithi Nakha, Chhat, and Nadiparwa, during which people not only take holy baths but also clean rivers, lakes and ponds.

Short-sighted solutions

As springs across the country are drying, the practice of lifting groundwater using electric pumps has become rampant. Several municipalities have declared themselves ‘drought-prone areas’ and allocated a budget for drilling tube-wells, deeply boring and lifting. Groundwater lifting using deep-boring technology is now on every local government’s agenda, even though few people knew about it until recently. It is one of the major causes for the drying of springs, as springs and water-lifting schemes share the same aquifers. Provincial and local governments allocate considerable budget for such activities, without taking into account that groundwater extraction might be ineffective and unsustainable in the long run.

Exemplary but insufficient

The silver lining is that a number of local governments are concerned about the drying of springs and realize this is a serious issue. Some local governments have started thinking about spring revival but are unable to put a stop to destructive practices such as haphazard infrastructure development.

Some municipalities have rehabilitated traditional ponds, established rainwater-harvesting systems, and launched programmes to augment spring flow. Physical interventions such as the construction of trenches, ponds, ditches, swamps, reforestation, etc. are also being carried out. About 50 percent of local governments covered by the NWCF-ICIMOD study have incorporated water source protection and spring revival activities in municipal plans and programmes, but they admit they lack the required technical expertise.

To help address this gap, NWCF and ICIMOD organized a policy dialogue called ‘PaniSatsang’on 16 October 2020. The event focused on ways to mainstream spring revival in policymaking and implementation at the local government level. Local policymakers and stakeholders shared their views on water resource management and conservation policies, practices, and alternatives. They highlighted innovative spring revival efforts such as the construction of recharge ponds, trenches and bunds, planting of trees, shrubs, and grasses, the building of temples, etc.

For example, Durga Devi Bhattarai, Deputy Mayor of Suryodaya Municipality, Ilam, talked about the ‘one ward–one pond programme, birthday tree plantation campaign, restrictions imposed on heavy equipment used in infrastructure development, and the prohibition on pesticide and chemical fertilizer use around springs. HarkaBahadur Saud, Chairperson of Chaurpati Rural Municipality (RM), Achham, said the RM has already constructed 2000 recharge ponds and carried out tree plantation programmes. NanuGhatane, a spring conservation activist from Namobuddha Municipality of Kavredistrict, shared how the dried-up spring in her municipality revived a year or two after her conservation group built a pond in the recharge zone. Their stories offer valuable lessons on spring revival and their efforts should be supported and replicated widely.

A way forward

To mitigate the crisis of drying springs, local governments, community groups and technicians/experts should make concerted efforts for a spring revival. An effective spring revival programme requires the participation and coordination of multiple actors at the local, provincial and federal levels. Spring revival measures and related capacity building programmes should be incorporated into municipal plans, taking into account gender equity and social inclusion. There is a need to enhance local capacity in the hydrogeological assessment so that locals can identify recharge areas. A spring conservation network, locally referred to as Pani Heralu (Water Watchers), has been initiated in some municipalities, and it should be expanded to promote good practices. Incorporating spring revival in school and college curriculums would also be useful. It is equally important to use available water efficiently, assess groundwater availability and use, and monitor and improve water quality.

Madhav Dhakal works at ICIMOD and Chiranjibi Bhattarai, BhumikaThapa and Sushma Tiwari work at NWCF.