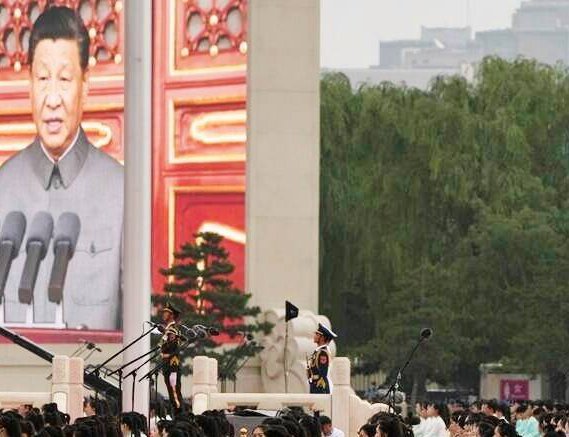

On July 1, the Communist Party of China (CPC) celebrates its centenary. Jude Blanchette and Evan S Medeiros write in their recent essay in The Washington Quarterly, that this is happening at a time when the Party commands more wealth, power and global influence than at any point in its history. The role of one instrument — the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) — in establishing, consolidating and expanding the Party’s power is widely researched and, therefore, well known. The role of the other, the United Front Work Department (UFWD), is barely understood and, thus, underestimated.

In October 1939, when the Communist Party was still a group of rebels, Mao described the UFWD as one of the three jewels (or magic weapons) of the communist movement (the other two being the Party and PLA). While the PLA was involved in fighting its way to power, the UFWD engaged in political influence-type activities that portrayed the CPC as a benign, progressive and democratic force. Its underlying philosophy spelt out by Mao in October 1944 was that the work of the United Front was to first unite with various social groups, and then to convert them and transform them. In line with Mao’s dictum, the UFWD performed the important task of building temporary alliances to overthrow the Chinese government and install the Party in power.

After 1949, the Party turned its attention to the three territories of Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan. United Front tactics were adopted especially under Deng Xiaoping through, among others, the Office of Hong Kong and Macao Affairs, Taiwan Affairs Office and Xinhua News Agency. Elements within the ethnic Chinese populations in these territories who were sympathetic to the CPC were mobilised to harness support for the Party’s cause among the local population, especially after Deng opened negotiations with the British and Portuguese for the return of Hong Kong and Macao respectively. The idea was to build pressure from “within” on the colonial powers by creating pro-unification public sentiment in order to erode the legitimacy of foreign rule. The UFWD invited scores of opinion makers to China, gave them privileged meetings with the leadership, helped their businesses and, in return, asked them to act as influencers in the local population. The peaceful “return” of Hong Kong and Macao in 1997 and 1999 owes as much to the UFWD’s work as it does to the skilful negotiation.

As China’s global influence grows in tandem with its economy, the UFWD is now being pressed into the service of the Party’s external operations. People in India might think that this is limited to countries with significant overseas Chinese populations. Yet there is sufficient reason to believe that the surge of outreach efforts that are orchestrated by the UFWD are in fact influence operations to promote the CPC’s political goals even in countries that do not have significant numbers of ethnically Chinese citizens. With this objective, since 2015, the UFWD is being honed into a major instrument to enhance the Communist Party’s discourse power abroad.

Consider these developments. In May 2015, a national conference on United Front work was organised after nine years. New regulations were enacted to enhance its authority to operate externally. The UFWD has been given direct control over key agencies that might act as overseas influencers, such as the State Administration for Religious Affairs, the State Ethnic Affairs Commission, and the Confucius Institutes. The Party also created a new Leading Small Group with General Secretary Xi Jinping as the head, signifying direct control and command from the very pinnacle. The Party’s leadership last month held a special study session for the Politburo, to underscore the significance the Party attaches to the proper narration of the “China story” abroad in ways that strengthen the CPC’s discourse power and shape international public opinion in its favour. These developments suggest that the Party is prioritising a major surge in influence operations globally as it moves closer to the “centre of the world stage”. The UFWD will be the key actor.

Beyond the general effort to foster a benign and positive image in international public opinion through “feel-good” stories, the UFWD is bent on creating a common cultural narrative in Eurasia. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its ideological twin, the Community of Shared Future for Mankind, are more than just foreign policy doctrine. They represent the Party’s attempt to define China’s leading role in Eurasia with a view to diminishing the salience of other civilisations. In this context, a key CPC goal is to build influence at the ideational level through Buddhism as a cultural resource in order to create a common cultural narrative in Eurasia. For example, a recent essay by Gregory Raymond of the Australian National University focusing on the UFWD’s influence operations in south-east Asia, shows how China courts senior members of the Buddhist clergy to foster a collective cultural connect, and how efforts are underway to include Buddhism in the BRI in order to potentially create a conduit to influence political decision-making. This observation is equally relevant for India which has a significant Buddhist population in states bordering China, as well as for the three neighbouring countries (Myanmar, Bhutan and Nepal) which are either Buddhist or have a historical and cultural connect with Buddhism. Such efforts are all the more sinister when the CPC claims to be staunchly atheist and forbids its own members from practising religion.

The centenary, thus, is a timely reminder of the pressing requirement for broader China studies in India beyond the focus on the PLA in the context of the boundary question and, to some extent, on China’s foreign policy in South Asia. The paucity of public literature on the CPC’s activities through mechanisms like the UFWD needs to be redressed as soon as possible in order to comprehend the magnitude of the challenge that India potentially confronts in the coming decades. Indians can no longer afford to have a superficial understanding of their largest neighbour and would-be hegemon.

This column first appeared in The Indian Express’. The writer was India’s ambassador to China and Foreign Secretary