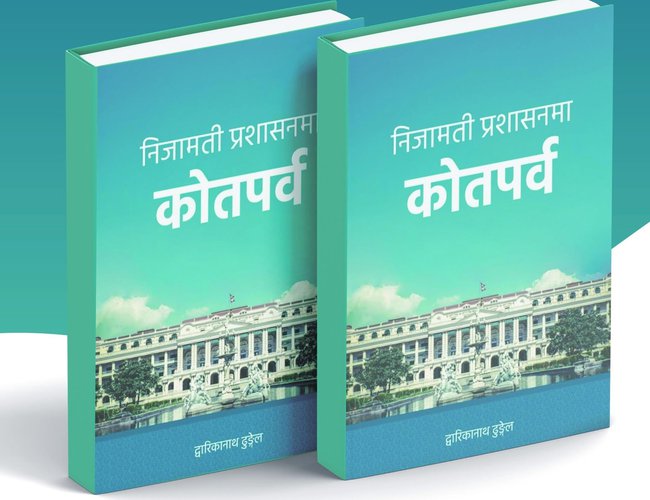

The recently published book entitled "Nijamati Prasasan Ma Kot Parba" (Massacre in Personnel Administration in Nepal) by Dwarika Nath Dhungel, a former career civil servant in the Nepal Administrative Service, is an important work that dissects the internal dynamics of administrative reform efforts, particularly in personnel administration, in Nepal over a span of about 40 years. The book focuses on the efforts of the Girja Koirala Administrative Reform Commission, of which the author was a member secretary, aiming to establish a compatible administrative system with the multiparty political system.

The author is a prolific writer in the field of Public Administration, with other significant works such as "District Administration: My Experiences in Nepal" and "Chakrabu ma Nepal ko Jalsrot." These earlier books are considered classical and outstanding in the field of Nepalese Public Administration. The title of the current book, "Nijamati Prasasan Ma Kot Parba," reveals many hidden stories of Public Administration development in Nepal from both historical and contemporary perspectives. The term "Kot Parba" holds special significance in Nepalese history, symbolizing palace conspiracies and the culture of competition, conspiracy, and annihilation of opposition groups. This culture has persisted throughout Nepal's history since the 1840s and continued during the 104-year Rana Regime.

During the Rana Regime, whenever a new Rana Prime Minister assumed power, there would be a reshuffling of administrative personnel. The supporters and loyalists of the new prime minister would be appointed to key positions, displacing those who were aligned with the previous prime minister. Therefore, readers of this book must understand "Kot Parba" as a cultural trait ingrained in the politico-administrative culture of Nepal.

This book contains the history of personnel and administrative development, especially after the political change in Nepal in 1951.

The author has carefully documented the efforts to transform the Nepalese administration from the Rana Regime's patronage system to newly initiated democratic values and norms for a parliamentary system. A neutral bureaucracy based on merit, specialization, and quality was envisaged. A vacuum in the Nepalese administration was felt, especially in the lack of trained manpower to run the administration of the new political system. The author has elaborated on the assistance of personnel provided by the Indian government to run the Nepalese administration. The Secretary of King Tribhuvan and the Cabinet Secretary were appointed from among Indian Administrative Service personnel. Meanwhile, Mr. Matrika Prasad Koirala, then Prime Minister, requested the government of India to depute Indian civil servants to help run the Nepalese administration.

N.M. Buch's report is mentioned in the book to indicate how the report suggested bringing personnel to administer different departments of Nepal. If the Buch committee report had been implemented, it would have been more difficult to send back those personnel than the Indian Army personnel posted on the northern border of Nepal.

The Interim Constitution of Nepal 1951 envisages the establishment of a parliamentary system. With this political change, efforts were made to create a neutral bureaucracy. The provision of the Public Service Commission was incorporated in the Interim Constitution for the recruitment of capable officials in the administration of Nepal. In the course of time, dissatisfied low-salaried civil servants staged a strike to raise their salary. The then Home Ministry issued a notice stating that civil servants are not allowed to be members of political parties and not allowed to stage such strikes. The Home Ministry enforced the value of a neutral civil service in conformity with the parliamentary system. The Civil Service Act came into existence in 1956 and regulations thereafter. The Civil Service Act also incorporated the spirit of a neutral and professional civil service.

Mr. Dhungel elaborates on the results of the four historical administrative reform commissions that were constituted during different periods. The Reform Commission instituted under the leadership of Prime Minister Tanka Prasad Acharya took the strategy of introducing fragmentary reforms and decided to implement them immediately. Hence, there is no single report called the Commission Report in the commission headed by Prime Minister Tanka Prasad Acharya. This commission could implement what they proposed to introduce. One of the recommendations was the establishment of the Institute of Public Administration, which could not materialize to train the civil servants of that time. The dream of the Institute of Public Administration for human resources development could be partially realized by the establishment of CEDA and the Administrative Staff College as an autonomous institute under the government.

Before the Koirala Reform Commission, two other Administrative Reform Commissions were instituted. They were the Beda Nanda Jha Commission Report and, after that, the Bhekha Bahadur Thapa Commission Report. However, the main focus of the book was on the process and procedures of the Girja Administrative Reform Commission report. This commission was established immediately after the institutionalization of the multi-party parliamentary system in Nepal. The entire administration of Nepal was to be reformed to conform with the parliamentary system. Under this new system, the bureaucracy was supposed to be a neutral institution to serve the governments of different political parties. The civil servants were no longer neutral. The government in power intended to appoint only those political party-trusted people in administrative positions. The author mentions his own experience and the opinion of ministers about him supporting the communist party; hence, he should not be given a role in the congress government.

The author mentions in his book that the vice-chairman, Mr. KulShekhar Sharma, of the monitoring committee under the Prime Minister had discussions about implementing the provisions of recommendations, including the recommendation to downsize the bureaucracy.

In the meantime, the Prime Minister, who is also the chairman of the reform commission, informally secured the list of civil servants from the Ministry of General Administration and selected those who were "our people" and "not our people." The Cabinet was made to amend the regulation so that civil servants who had served 30 years in the Nepalese administration or who had completed 58 years of age would be retired compulsorily. This act was not made known to the Monitoring Committee. This act resulted in the forced retirement of hundreds of senior and professional civil servants. This was an action from an extra-bureaucratic channel without taking into confidence the members of the Reform Commission. In this process, according to Dr. Dhungel, there were three Secretaries in one day in the Ministry of General Administration to undertake the mass retirement event. This action is symbolically called "KotParba."

It might be because the majority of members of the commission were former veteran administrators, so PM Girja Koiral had difficulty trusting them and decided to take such drastic action on his own with the support of his party people.

The then government went against the established norm by making forced retirements for many civil servants in one stroke. A human being in an organization holds multiple roles as a citizen with voting rights, a family member, and a member of a larger society. Their performance depends on many factors. In personnel management, a clinical approach has been practiced since the 1940s. Administrative behavior studies show that removing a person from an organization is a cost rather than a gain. It incurs a lot of resources to train a person, and once they are dismissed from the job, it means a loss to the organization.

One of the retired civil servants, Mr. Shiva Bahadur Nepali, from the agriculture cadre, told me that this "Kotparba" has broken the backbone of the agriculture cadre, which has not yet been filled by the Ministry of Agriculture even in 2025. Similarly, Dr. Tirtha Bahadur Shrestha, a renowned ecologist of Nepal, said that he was appointed to enter government service during PM B.P. Koirala's tenure and was forcefully retired during PM Girja Prasad's time.

Another long-term impact of the political change in 1946 is the establishment of civil servant unions in each department and office based on political parties. This practice of political party-based unions in the Nepalese civil service allowed for several party-based unions in each office, creating a party-based management system in the Nepalese administration. Such a system is not available anywhere else except in Nepal. The Whitley Council in the British civil service is only meant to campaign for the welfare of personnel, not as political party-based unions.

While serving as secretary in the Ministry of General Administration, the author mentions the assurances given to him by the then prime minister and deputy prime minister that the civil service is to be kept away from unnecessary political party influences and allowed to run neutrally. However, the Minister of General Administration at the same time used to decide placements and transfers based on party directions.

The culture of political parties controlling the bureaucracy continued.

The present Constitution of Nepal does not allow for a majority government, so political parties have to form a joint government. Ministries are divided among political parties, and ministers select secretaries who are sympathetic to their party. When the government changes, a new set of secretaries is appointed based on the trust of the ministers. The concept of cadre civil service and professional competency is hardly recognized. There are reports in newspapers of positions in the administration being traded for cash, disregarding competency, integrity, professionalism, and loyalty in civil service. In a multiparty system, a one-party bureaucratic structure cannot function effectively, as seen in the Nepalese bureaucracy. A neutral bureaucracy might be the solution.

Political influence has infiltrated all sectors, including appointments to key positions like joint secretaries, secretaries, and Chief District Officers (CDOs). This culture has discouraged civil servants from being innovative, taking risks, and making neutral decisions. They become instruments to implement the wishes of the ministers. Nepal has a fluid political system that does not provide stable government, making civil servants pawns of political parties. When a new political party comes to power, a new set of civil servants is brought into the administration. Ministers are often portrayed as clean in behavior and character, while civil servants are blamed for non-performance and malpractices.

One of the important questions that comes to mind is why administrative reforms cannot take root in the institutionalization of reforms. Why are reforms often aborted?

There are usually two parties involved in implementing administrative reforms: bureaucracy and the political system.

If politics is in favor of administrative reform but the bureaucracy is not, the reform can only be partial and fragmentary. Similarly, if politics is not favorable but the bureaucracy is, partial reform is possible. If both politics and bureaucracy are not favorable, no reform is possible. In the case of Nepal, only fragmentary administrative reform has been achieved.

This book discusses politics, international relations, culture, intra-bureaucratic conflicts, and the administrative history of Nepal. The author's tenure in the Ministry of Land Reform allowed him to learn about the intricacies of land administration and the role of Guthi Santhans in managing guthi land in Nepal, as well as the financial support provided by Guthi Santhan for maintaining religious and cultural rituals both within Nepal and outside of Nepal.

Two other important aspects of this book are: 1) the methodology used in writing the book, and 2) the documentation of valuable public documents. The methodology used in this book is based on the Jiro Kawakita method, which includes detailed events to allow readers to judge the results. This book serves as an autobiography of the author's life during his service in the Nepalese bureaucracy, where he also analyzes the events. His courage to provide vivid descriptions of events during those days is commendable. Many of his experiences, both sweet and bitter, are recorded in the book.

Another important aspect of this book is the inclusion of valuable documents that are not easily accessible. The documents in the appendix make this book special and unique. It is a valuable resource for researchers, administrators, politicians, and the general public. This book is an important jewel in the literature of Nepalese Public Administration.