Cultural Theorist Michael Thompson of IIASA says interesting ideas emerge from the periphery and not the center. This is because the center (of global order or dominant civilization) is a prisoner of its own hype, political correctness if you will of both its left and its right. The periphery is not bound by those shackles and is free to think the unthinkable. I came across ideas that demolished comfortable assumptions (in the form of two books) that shook my own thinking twice in peripheral Pakistan, the first time a dozen years ago and the second time in January this year.

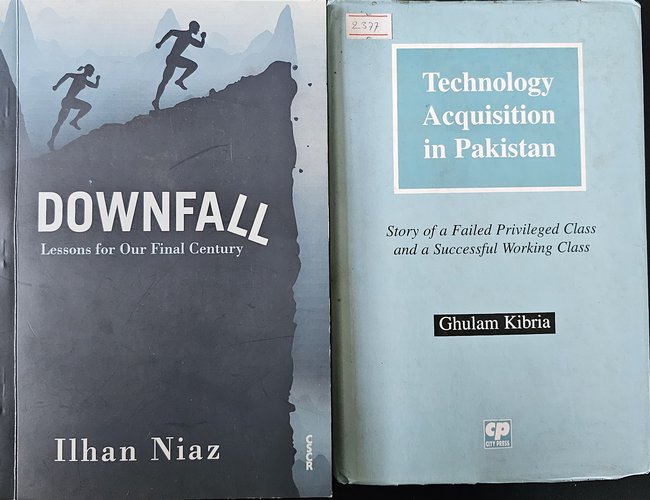

In a meeting in 2012 organized by Pakistan’s Planning Commission and its Academy of Sciences on the country’s energy options, I came across in the conference’s bookstall a book by Ghulam Kibria titled Technology Acquisition in Pakistan: Story of a Failed Privileged Class and a Successful Working Class, published in 1998 by Karachi’s City Press. Kibria is no relaxed ivory tower academic: born in pre-Partition Raj and an engineering graduate of Aligarh Muslim University, he gained shopfloor experience in Europe before returning to Lahore to start his own machinery business and eventually becoming an activist with the famous Orangi pilot project and Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER).

The book’s sixteen chapters begin by trying to understand technology and how its modern version was helped into being by the nature of British society that saw the beginning of the industrial revolution. It then travels the globe, looking at how countries that successfully industrialized such as Japan, China, Korea, Thailand and the Soviet Union acquired and internalized modern technology. What is insightful in these descriptions is how technology was NOT transferred out of goodwill of the industrialized West but was developed indigenously through reverse engineering as a response to colonization.

Non-trade barriers have been put up against such indigenous efforts through the system of intellectual property rights. In what resembles continuing neo-colonization, such efforts at indigenous development are labeled as theft, even as it must be remembered that the industrial West too engaged in such “theft”. That is the history of silk and tea “stolen” from China (recounted by Alan Macfarlane in his 2003 The Empire of Tea (Overlook Press, New York)) or the better flour griding technology stolen from Hungary in the 1870s by the main American grain traders Pilsbury and Washburn (described by Dan Morgan in his 1979 classic Merchants of Grain: the power and profits of the world’s five giant companies at the center of the world’s food supply (Viking Press, New York)).

The book then describes how, in sharp contrast to say Korea or China, Pakistan, which inherited from the British a very rich technology base, especially in the mechanical engineering of railways, squandered that capacity and failed to progress. Rather than promoting the country’s very creative mistris through social, institutional and legal reforms, its elites and middle class aligned with the military to retain a suffocating feudalism, which condemned it to remain the periphery of capitalist West. Proving this point, the book begins by tauntingly recalling the country’s military dictator Ziaul Huq and his early 1980s visit to Japan’s Toyota factory. The general formally asked the Toyota management to share its management technology with Pakistan; but the Toyota president, with very Japanese courtesy, politely reminded the dictator that if they did so, “where would we sell our cars?” In another incident, an electronics mistri in Karachi was asked by a visiting World Bank team from whom he acquired the technology: the mistri asked the translator if the sahib was mad not to realize that no one give away technology, that he had mastered it himself. The basic message in all of this for the entire developing Global South is that technology is capacity whose entire ecosystem must be painstakingly built bottom-up indigenously and simply cannot be transferred.

In January this year, I was invited by Islamabad’s Center for Strategic and Contemporary Research to a conference on rethinking disaster risk management in South Asia, where I came across their remarkable publication Downfall by Prof. Ilhan Niaz, who is professor of history at Quaid-i-Azam University. It is a historian’s heavy-hearted take on the inevitable civilizational collapse (unless very difficult countermeasures are taken that he outlines at the end) from the interlinked calamities of climate change-induced global warming and biodiversity loss, both fueled by the blind pursuit overconsumption and limitless economic growth.

Drawing on insights from scholars of yore – Herodotus, Ibn Khaldun, Voltaire, Malthus, John Stuart Mill and Darwin – and referenced with 206 detailed endnotes for a book of only a hundred pages, his first chapter begins by debunking the widely held belief that the impending crisis was unforeseen. Past thinkers mentioned above have clearly foretold that, regardless of formal political systems, plutocratic elites who have a grip on power have historically been blinded by decadence that prevents them from taking difficult but wise decisions to save their civilization, the planet and humankind with it.

Puffed up by baseless optimism of quick panaceas, they revel in seemingly Green measures that are meaningless. Despite awareness of plastic pollution, we recycle only about a tenth of it with “the rest dumped into landfills and water bodies to result in more plastic than fish in our waters by 2050”. Also, while the blame game about who the biggest CO2 emitters are is routinely traded between countries, the truth is “just 100 companies (mostly Western) account for over half the (cumulative) GHG in the atmosphere since 1850”. This has serious implications for the current panacea on the table: assigning blame for loss and damage to compensate those who are damaged. How will that initiative be moved and (obviously) resisted by the global 1% primarily benefitting from this cost externalization to the environment and the marginalized poor?

One of the strongest essays is on the myth of endless economic growth that economists and policy makers in thrall to it labour under, seemingly oblivious of the massive contradictions that underlie that belief. In 2010, the global average per capita income was $8500 just at the point where humankind’s consumption of natural resources had reached the upper level of what the Earth can renew. Currently it is $11000, and resource extraction has crossed any stretched concept of sustainability. Rather than demonstrate sane statesmanship to limit growth and resource extraction at the $8500 level even while leveling out socio-economic inequality and allowing civilization to avoid ecocide and collapse, the dominant current mantra is more unlimited growth. The author argues in his other essays that it will only lead to geopolitical wars and retreat into some kind of fascism and tribalism by 2100 – and collapse of civilization as we know it much more widespread and horrific that that of Roman or others – if major course corrections are not enacted between now and 2035.

Having laid out the apocalyptic scenario – and the drivers leading to it – the author concludes with very tough measures that need to be taken to avert the global disasters. The first is to pick up the from the works of Fernand Braudel and others to acquire a heightened historical consciousness away from the present-minded individualist vacuum. This would lead to abandoning the suicidal fascination with endless economic growth of contemporary capitalism to a more well-being oriented stationary state. It would also need countries to abandon what are obviously petty squabbles in light of the massive apocalyptic darkness staring back at us. Retreating into growing insularity and xenophobia or cold war will be suicidal. It is time to pay the bill for the wild, resource-prolific partying of 1975-2025, but it can be done if the science and technology we already have can be used not for growth based on senseless globalization but on localization of much of production to meet everyday well-being needs. These measures would require not popular (and populistic) leaders but wise ones in the Platonic sense, which in turn would require us to move away from “democracy” as currently propagated to one of wise and just governance.

On the face of it, these are very tall orders demanding near complete reordering of global governance as prevails today; but the ominous day of reckoning facing humankind is no less colossal. Ignoring it will not save the coming generation and what remains of the current one from the impending disaster. Download the book from the link above, read it, mull over its message, debate them with friends and colleagues, and think about how we can all reduce our consumption footprint while maintaining basic decent living to serve the larger purpose of human and planetary well-being.

Dipak Gyawali

Gyawali is Pragya (Academician) of the Nepal Academy of Science and Technology (NAST) and former minister of water resources.

- West’s Electoral Turmoil: Implications For Emerging New World Order

- Jul 14, 2024

- Did Modi Lose Even When Winning?

- Jun 12, 2024

- As You Step Out Into The Real Wide World Of New Challenges…

- May 23, 2024

- Unfolding International Disorder & What It Portends For Small Countries

- May 08, 2024

- World Social Forum: Rethinking and Redefining Development Itself

- Feb 21, 2024