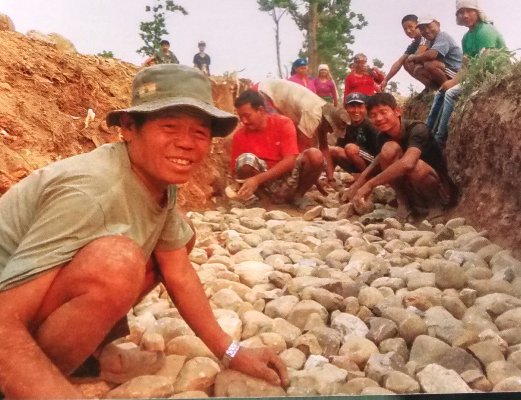

The National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA), approved by the Government in September 2010, opened avenues to implement climate change adaptation projects in Nepal to address the most urgent and immediate needs of the climate-vulnerable communities and natural resources. 'Stand-alone' approach of implementation, non-integration into the planning process, and target monitoring indicate positive outcomes with little effectiveness and replication potentials beyond the project duration. Issues are frequently raised whether these projects are producing good results and have addressed the identified and most prioritised problems and challenges effectively.

Recalling the past, project development requires several brains to address identified, perceived and prioritised challenges and attain better results to respond to the needs of needy, marginalised, economically poor and vulnerable communities. Project development undergoes several steps. A climate change adaptation and resilience project is considered and recalled here to better understand project development and outcomes of implementation.

Once problems and challenges are realised at different levels, the first step is to link with national and local needs, priorities, and commitments. This provides a basis to conceptualise problem-solving projects or activities to respond to challenges and find an appropriate resource or people-centric ways to address the problem. Conceptualisation leads to project formulation, preparation of a project document, and negotiation at different levels with planners, budget allocators and decision-makers within a country or with development partners or funding agencies for financial support. Priorities of the sector agencies, planning, and decision-making bodies might differ and project developer faces difficulties to convince, primarily the financing institution, for funding at national, local or international levels.

National development proposals that seek funding from bilateral or multi-lateral sources are reviewed at different levels - regional and international and sometimes person or institution conceptualising or developing project documents may not know the state of a proposal in countries like ours. Several institutions, if authorised by the national government, exist at the national, regional and international levels to prepare, submit, and negotiate the project, and channelize the financial resources. Concerns, perceptions, needs, and priorities might affect the original concept of the development proposal.

Nepal accessed over US$ 80 million for Pilot Programme for Climate Resilience (PPCR) from the World Bank operated Climate Investment Fund. A group of 'Kathmandu-based elites' made efforts to 'blame PPCR as the loan project' and sounded much saying 'no loan to climate change. In my recall, only one person, engaged in energy and climate change activities, urged to access this fund and best utilise to address climate change impacts. This 'no loan to climate change' issue was also raised in the then parliament, and the then Secretaries of the Ministries of Finance and Environment professionally briefed the project to the Parliamentary Committee on the Environment. The then Minister for Finance Bharat Mohan Adhikary was also briefed about the possible outcomes of this funding and the Minister approved to access this Fund. Many of the '2010 elites' who opposed to accessing it contributed a lot in implementing climate change projects funded under this Fund. Funding for one of the components of the project was also used to construct the new building of the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology.

The then Ministry of Environment implemented a component on mainstreaming climate risk management in development and funding was channelled through the Asian Development Bank. The original concept of developing human resources, generating knowledge, and integrating climate risks into sector-specific policies, programmes and facilitative instruments was approached. After the human resources and necessary country instruments (policies, standards/norms, guidelines and manuals etc) are in place, the original idea was to develop multi-million dollars projects to address climate change impacts in key economic and social sectors climate-resilient was not materialised. This USD 7 million projects developed 6 concepts for less than USD 3 million (https://www.spotlight nepal.com/2016/12/16/climate-change-operationalizing-concept/).

There might be several reasons for the non-achievement of the project outcomes as conceptualised and planned. Few reasons might be: (i) those involved in developing a concept and project document were either transferred or sidelined or retired or were not in a scene; (ii) those engaged in implementing the project did not understand the concept and spirit of the project document; (iii) implementing agency did not want or try to discuss for better understanding (concept and project outcomes); (iv) 'close-door approach was followed during project implementation; and (v) technical matters were rather addressed non-technically and/or leading institutions or person overlooked important elements as well. This might be one of the reasons for not having project outcomes effective and replicable. Termination of the project leads to forget the outcomes. Similar activities are repeated in similar types of projects. This leads to again 'starting point'.

A similar situation exists in implementing approved project-level environmental assessment (EA - Initial Environmental Examination or Environmental Impact Assessment) reports. EA is, in many cases, carried out independently without functional coordination with the feasibility study and project design teams. Non-integration of the environment protection measures (benefit enhancement and adverse impacts mitigation measures), environmental monitoring and auditing in the project cycle or the detailed design of the project leaves the proponent multiple opportunities to benefit from this predictive tool. Some of the reasons might be: (i) environmental assessment is conducted as a 'stand-alone' study to get environmental clearance to implement the project; (ii) many proponents are unaware of the benefits of EA tool; (iii) some proponents might not know what is written in the approved EA report, what and how to implement; (iv) competent authorities do not allocate necessary funding for, or are unaware of the benefits of, environmental monitoring and auditing or consider their role to provide 'environmental clearance'; (v) competent authorities respond or take actions only in case of any complain registered; (vi) EA report preparers rather believe in 'influencing decision-making process' for approval than making a realistic and implementable report; and (vii) competent authorities enjoy and express willingness for being 'development-friendly by approving EA report of 'any quality such as the EIA report of Nijgadh International Airport.

If the situation continues, expected desired long-term outcomes as conceptualised or designed or negotiated or approved will not be achieved.

Batu Uprety

Former Joint-Secretary and Chief of Climate Change Management Division, Ministry of Environment (then), and former Team Leader, National Adaptation Plan (NAP) formulation process. E-mail: upretybk@gmail.com

- Approval Of EIA-Related First And Last Reports At Once

- Jun 14, 2025

- Two Calls For Climate Action From Kathmandu

- May 21, 2025

- Teaming up Climate Change Negotiation

- Apr 18, 2025

- Sagarmatha Sambad: Likely Bearing the Fruits

- Mar 27, 2025

- Decadal Experience In Preparing The NDC

- Mar 03, 2025