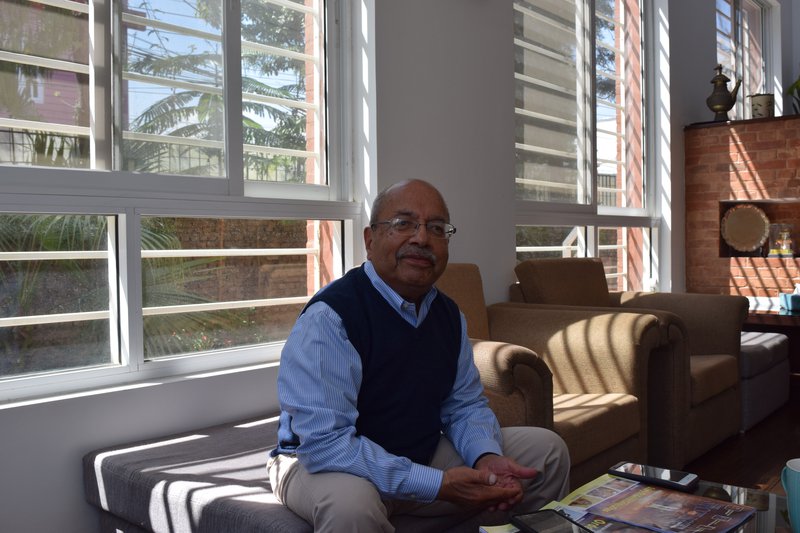

Born in Pyukha, the core of Kathmandu City, in the mid-1930s (that is, 1992 BS), Dr. Badri Raj Pande, in his childhood, saw dead bodies being taken along the streets near his house. Son of renowned scholar and former vice-chancellor of Tribhuwan University late Rudra Raj Pande, Dr. Pande today recalls that most of the dead included young mothers who had delivery-related complications.

Own Description

I was born in Pyukha Tole behind New Road. It was the heart of the city. I often saw the dead bodies carried by weeping relatives of Newar families. I would be stricken by grief to learn the cause of their death. The bodies were of women who had died during the delivery. I was concerned about the need for treatment and care to prevent the death of young mothers.

Fortunately, our house was close to the clinic of Dr. Jeet Singh Malla, who was also a friend of my father Sardar Rudra Raj Pande. Our family had very good relations with Dr. Malla. I used to visit his clinic whenever I got sick. During my visit, I used to discuss the issue with him. The health model of that period was not related to preventive care. Dr. Malla used to smoke Du Maurier cigarette, an expensive brand of that time. As a child, I used to ask him, didn’t smoking harm his health? Was it sweet? His answer was simple: the smoke of the cigarette killed the germs. This was the kind of understanding of smoking. I completed school with high scores in SLC, and joined the science stream with biology to study Medicine as per the practice of that time. Those with a mathematics major used to choose to engineer for further studies.

In the 1950s, there was no other way but to apply for a scholarship for higher education. I had secured the board rank in SLC and a high score in ISC and applied for MBBS under the Colombo Plan. Under an open competition run by the Public Service Commission, I was chosen for the MBBS course. I left Nepal in 1953 to study at G. R. Medical College. One subject there was Public Health and Hygiene in the fourth year. The areas of focus under that subject were safe drinking water, sanitation, waste disposal, pit latrine, and personal hygiene. From the third year onwards we had to study different diseases and it included etiology, pathology, diagnosis and treatment. However, we had little knowledge about preventive and even curative aspects because there were a very limited number of medicines.

Prevention of Obsession

Young Pande had always been thinking about the need to focus on prevention since his childhood. He was determined to study medicine and contribute to preventing the death of young mothers.

His family friend and neighbor Dr. Jeet Singh Malla were instrumental in shaping his views as he would also quietly observe Dr. Malla’s interactions with patients and treatment.

Coming back from studies, Dr. Pande joined government services and retired three decades ago. But his quest to save the life of mothers and children still continues. He chairs the national Certification Committee for Polio Eradication of GON/WHO and has visited different parts of Nepal.

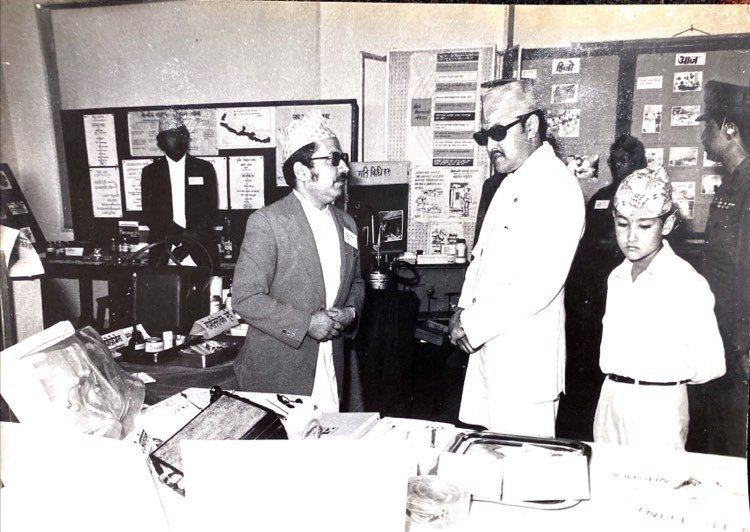

Dr. Pande with late King Birendra and crown prince (File Photo)

With his inner determination to study and watch how to prevent trauma and deaths of young mothers and epidemics like cholera, typhoid and jaundice, Dr. Pande has been an eye witness to the transformation of Nepal’s health system.

With the spread of coronavirus all over, Dr. Pande narrates the evolution of Nepal’s health system recalling his old days of Kathmandu and its inherent strength.

Despite decades of uncertainty and institutional upheavals, Nepal’s health system has evolved to give hope of even reaching the grass root level to inform, identify and treat the affected people.

Dr. Pande holds the view that Nepal has well-built modern institutions with sub-health posts, health posts, primary health care centers, district hospitals and regional hospitals and thousands of grass-root health workers like Female Community Health Volunteers.

Family planning promotional activities File Photo

“Nation-wide networks of health institutions and community-based health workers and their reporting system remain a strong pillar of Nepal’s health system. They will be useful in the context of contact tracing, quarantine, isolation and treatment during the Covid-19 crisis,” says Dr. Pande.

Practices of Isolation

Dr. Pande said that the restoration of some of Nepal’s old cultural practices can help fight pandemic like Covid-19. “We have our own practices of physical distancing while greeting with folded hands (Namaskar), quarantine and isolation during the meeting of sick and cremation. Hand washing, rinsing the mouth after meals were parts of our life. We used to wash hands before eating food and after visiting the toilet regularly and were important, particularly in Brahmin families. We used to have separate dress codes for lunch, dinner and a separate kitchen. So much for the good practices!

“But because of westernization, we even gave up our own good practice of society and life.”

Family Life

Living in Maharajgunj in a quiet bungalow with his wife Pramila and son, renowned dentist of Nepal Dr. Neil Pande, daughter-in-law Dr. Banu and grandsons, Dr. Pande, at 85, begins his day from early in the morning, from 5:30.

Then he spends the latter part of the morning with the family; his grandsons have gone abroad for further education. Despite his busy schedule, his son Dr. Neil Pande regularly spends time with his father, who is still busy attending various programs and social events.

“I believe in a healthy lifestyle. Think positive. Moderation all around is always good. My motto is - health is self-care, look at yourself. For this, you need to have certain good habits,” Dr. Pande narrates.

His son and daughter follow his path. However, there is going to be some gap now. “I have two grandchildren. However, both of them have said they don’t have any interest in medical or dental fields. Looking at my time as a medical doctor, they are much better off and it is incomparable now. In my family, my father was an educationist. One of my nephews is a medical doctor in the United States.”

Childhood Memory

When I was a child, New Road was very different. Just opposite to my home, there used to be farmland and farmers grew cauliflower, cabbage, corn, pumpkin, spinach and so on. Only a few households had toilets and most of the people used the open space. Even those with toilets did not have water carriage system. A tin container was put under the hole of the pan.

Kathmandu used to be very un-hygienic. The sweepers used to visit home and they changed the tin container every day. They carried the feces using hand without cover and supplied it to the farmers as manure. The scavengers used to get free vegetables from farmers as barter for the human excreta. As a resident of Pyukha, I can still speak little Newari. As I have seen the most unhygienic part of Kathmandu, I always give priority to hygiene in life.

Journey to MBBS

Although his family does not have any history of involvement in the medical sector, even in the traditional medical sector, Dr. Pande is the first in his family to serve in the medical sector.

As he had a strong determination to pursue the medical course, Dr. Pande passed the school examination and college examination one after another with very high scores.

Dr. Pande passed School Level Certificate Examination (SLC) at the age of 13 and completed ISc at the age of 15. Due to his age bar, he had to wait for one year to become eligible for MBBS study. Later he was selected under Colombo Plan to pursue MBBS.

Life in the Medical Sector

Dr. Pande returned with MBBS in 1958 from G. R. Medical College, Gwalior and joined the government service. Although Bir Hospital was the choice of all the doctors in Nepal during the period, he chose to go to work at Bharatpur Hospital constructed as a field-based hospital under the Malaria Eradication Project in Chitwan. However, authorities, who were earlier positive about his choice, denied him the chance and asked him to work elsewhere.

Frustrated by the official offer, he applied to work as a Medical Officer in charge of Dispensary for students at Saraswati Sadan. With a limited practice in the clinic, he started working in Shanta Bhawan Hospital as a volunteer in his leisure time.

In government service since 1958, serving in different positions in the government, Dr. Pande resigned in 1990 to join the World Health Organization. Since his retirement from government office and WHO in 1996, he has been active in the social and professional organizations to carry on his mission to strengthen Nepal’s health system to provide equitable access to health services including maternity and child health. He founded the Nepal Health Economics Association in 1998. As Chair of the Polio Certification Committee, he is still active in the polio eradication campaign.

Nepal’s Health History

“Looking back at our history of the last eighty years, what I can see is a drastic transformation. As a child, I had seen young mothers dying due to minor complications during delivery and many children dying before completing a year. Nepal has made a dramatic change in the vicious cycle.”

Following the revolution of 1950, Nepal took several steps with support from the US Government. Whether it be in Malaria control or Family Planning and reduction of child and maternal mortality, Nepal’s efforts are remarkable. However, institutional change in the health sector started a bit late.

“The decade between 2036-2046 was a golden decade in the history of Nepal’s health sector. During that period, Nepal had done a lot of work. The foundation of the current health system lied on the decision taken during that period. The health system sets a model with disciplined staff and harmonious relations. We maintained good rapport. Our staffers were highly committed. We discussed the likes and dislikes of the decisions. I always believed in openness and transparency and selection on merit basis. We disagreed but we worked for the country and organization. However, the situation is now more frustrating when I look at our junior colleagues taking decisions. There is anarchy and indiscipline. I get upset when we listen to our junior colleagues who are now in the leadership position.”

The system built during the career of Dr. Pande was one of the key reasons behind the progress in Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), in the area of reducing maternal mortality and infant mortality. This system is still working.

Pande’s World

“I have seen various phases of Nepal’s public health from the early days or before the 1940s till now. The health condition was pathetic in the early 1940s with a very high maternal mortality rate, infant mortality, and epidemics like cholera, typhoid, smallpox and measles were normal. There were neither curative nor preventive methods in place. Few doctors, with few medicines, and only a few people had access to health and was limited for highly privileged classes.

In the past, many pandemics passed through without due preventive and curative practices. However, Nepal is better prepared now with curative and preventive methods and medicines. Given the current epidemic of coronavirus, Nepal’s health system, particularly in the preventive side, is well established. I think the curative side will face a lot of pressure in case it is serious. However, Nepal can turn the situation in its favor through sound preventive policies. Given its vast pools of the health network, which has recently somewhat broken down due to new state restructuring of the grassroots level health system including FCHV, Nepal can make things different.

Discipline To Anarchy

My junior colleagues complain to me about the growing anarchy and indiscipline in the organization level nowadays. During our time, ministers were always afraid of staff and bureaucrats, who were consulted before taking major decisions. There were bad and good people during that time. In general, our organization was good. Recently, frequent interference by ministers and politicians has destroyed our health system. After the restructuring of the state, health seems to be no one’s priority. “I do still visit various districts under the Polio Campaign. I am on the chair of the Polio Certification Committee, which was previously held by Dr. Hemang Dixit. I have been heading to the committee since 2008. The committee was set up by the Ministry of Health on the recommendation of WHO. A few months back, I was in Janakpur for two days. I was informed that there is a lot of confusion in implementing health policy since federalization. The old structures were dismantled and the new structure is still nowhere. Well organized District Public Health Office and its units were either dissolved or handed over to the local level. In the past, they used to be under the supervision of the Department of Health and Regional Directorate. But now there is confusion in reporting and monitoring. In this crisis period, like Covid-19 Pandemic, Nepal might have to pay a high price for this disruption, unless quick actions are taken. Although dismantling of the regional directorate will have nominal impacts because they used to liaison, the district was the key to Nepal’s health system. District Health Officers were key and finally local. Of course, the districts were overburdened because of failure to empower the local level. Since there is no district health office and province has little say, the money directly goes to local level Urban or Rural Municipalities. Districts and provinces are helpless. There are no supervisions at all. In only a few places there are good things going on but in many places, the system has gone wrong. Our health system has got derailed and there is a gap in the information system.

Hope To Revive

The time has not gone out. We can still bring back our system by strong supportive supervision and activating mothers’ groups, FCHV, sub-health posts and health posts, cooperatives, and other small groups. We need to mobilize all these institutions. Self-care is very important in the health system. Large numbers of people are yet to have access to health. Those who have the money go all over the world but this is not for all. There is everything in the constitution including universal health rights. However, nothing is there in practice. The government is providing immunization free of cost this is good. But, hospital access is still a dream for a large number of marginalized populations.

Health Structures In COVID-19

As Nepal has been facing Covid-19, we need to activate structures that work. We are stressing for regular hand wash, though people don’t have access to water. Who can afford good quality sanitizer, unless the government provides it? I think they ought to do as there are places with an acute scarcity of water.. Where do people get tissue paper to cover nose while coughing or sneezing? Can poor people afford it? All these are good for western countries where you have water, sanitizer and soap. Even western countries are facing a shortage of tissue paper and sanitizer. We have been teaching people over the last 40 years to wash hands. How many people follow this? We have to be realistic. Instead of suggesting for tissue, we should have encouraged people to use elbows when sneezing and coughing from the very beginning. We need to ask people to carry on with reasonable and doable practice. Health should be self-motivated.

Hospital Capacity

There are a few good hospitals in Kathmandu but what about Jumla and Humla? We need to develop health systems catering to the people living in remote parts of Nepal. We need to concentrate on basic public health practices like waste disposal, water, sanitation and hygiene at all health facilities including the hospitals. These are priority issues that cannot be ignored.

Quarantine Not New

In the context of Covid-19, some of the practices prescribed by WHO used to be there with us in the past. Born in a Brahmin family, we do have a practice of handwashing after the toilet, touching things and before eating meals. After having, we had to rinse our mouth with water, indeed a good oral health measure! We were allowed to go to the kitchen only after washing hands and feet. We used to wear dhoti which needs to be a fresh one. Our kitchen used to have many restrictions. They were there to prevent the contamination of bacteria. After death, we practice going for 13 days of isolation. Touching the dead body by others than the sons, who are supposed to go in isolation, used to be considered a sin. Even after returning from the funeral, we are required to take the bath and wash all the cloths used during the procession. In a broad sense, this used to be a part of quarantine and isolation. Wearing white clothes puts the persons of the bereaved family for a yearlong quarantine. All these practices were taken to prevent the spread of diseases if any that could follow the death of a person. As we have given up our practice of self-quarantine and isolation, the westerns are practicing it now. Contradictorily, we are replicating these practices from the west. We did not understand the implications. Now we are.

Job Hunt

“As I was selected under a government quota, I had to go and work in the government hospitals all over Nepal. However, from the very beginning, I was very much interested in public health. When I returned from study under the Colombo plan, I noticed that everyone was interested to join Bir Hospital and it was his or her priority. However, I had asked a position in a field hospital in Chitwan. Although I was asked about joining Bir Hospital, I straightforwardly said no and conveyed my choice to them to go Chitwan Malaria infected area. During the time, the United States Office of Mission had been launching the malaria eradication program in Nepal and Chitwan was one of them. Under Malaria Eradication Program, USOM had also established a field hospital in Bharatpur. My interest to join Chitwan was unbelievable to the officials. They asked me to start working voluntarily in Kathmandu for a few months while accepting my proposal. I was appointed as Medical Superintendent of Civil Medical School. Which was just close to Bir Hospital. I accepted and started to teach the compounders, dressers and other health workers. It is good to recollect that many popular compounders of that time Uma Malla, Dayananda Vaidya were the products of the school.

Bir Hospital

As the school was next to Bir Hospital, I used to visit Bir Hospital where the situation was very pathetic. As we studied in more organized medical colleges and hospitals in India, I saw Bir Hospital as one of the most disorganized hospitals of that time. There were stray dogs and patients staying in the same place. The environment was so humiliating for the patients. Looking at the scenario, I decided I would never work in this hospital. Although everyone aspired to be working in the hospital, because that was socially prestigious, the environment of the hospital discouraged me very much. The state of Bir Hospital justified my choice to go to Chitwan. However, the officials of the Ministry of Health later declined my offer to go to Chitwan and asked me to go elsewhere. Providence had it, I was posted to the Bir Hospital as deputy medical superintendent and still later as Director of the hospital.

Shattered Dream

However, the officials broke their promise for unknown reasons. I declined to go to the offered posting. Although my father was in a good position and well known, I did not bother my father with this. As I was very much in a dilemma about my career, I had got an offer to serve as a Medical Officer in charge of student medical dispensary in Saraswati Sadan opposite Trichandra College. At that time students were in a strike demanding a qualified doctor at the dispensary.

As students were agitating, the Department of Education was searching for a doctor. At that time the Director-General of the Hospital was Dirgharaj Koirala and I contacted him showing my interest to work in the college. When I made my offer, Koirala did not believe it. He said I found you as a god while searching for a stone. He took me to the Minister’s room the next day. As the student agitation was underway, all of them were excited. Immediately, I applied for the post and my file moved to the Ministry of Education, where the minister was Parshunarayan Chaudhary. He approved my appointment.

Career At College

Following this, I went to the Department of Health and showed my appointment letter. However, they insisted on me that I had to go to a place where they asked me to go. Minister Chaudhary had to move my file to cabinet headed by B.P Koirala, the next day I was asked to join the office. Despite the opposition from Minister for Health Kashi Nath Gautam, Prime Minister Koirala intervened and accepted the proposal of Minister Chaudhary to send me to the college. This was the way my career began in Civil Service. Gautam was a simple person and he was misguided by other officials. “When I joined service, there were epidemics of typhoid and cholera. I felt my responsibility to launch TABC Vaccine. I used to lead the team of compounders to administer TABC vaccine to young children in school. This was a good experience for me. I had bought a cycle for my work. As I did not have much clinical work in college, I started volunteer work in Shanta Bhawan Hospital. I cycled down every Saturday and every morning from 7 to 10 AM. Shanta Bhawan Mission Hospital was well established at that time. Besides, I used to teach Physiology to graduate students taking up Home Economics at Padma Kanya College. As I had time, I also organized the founding of the Family Planning Association of Nepal, besides participating actively in the Nepal Medical Association.

Move To London

After completing my two years, the Department of Education offered me to go to the United Kingdom for postgraduate study in child health and provided me a scholarship from the British Government under the Colombo Plan. I recollect how I traveled by ship to the UK and it took seventeen days to reach London. I had clinical attachments in different hospitals in London in preparation for appearing in the examination for the Diploma in Child Health (D.C.H.) besides attending different courses. What I realized was that the focus on Paediatrics was not only on clinical perception and curative action but it also involved preventive aspects. Child health includes nutrition, immunization and protection. This included hygiene and so on. This also included managing the mental deficiency of children or autism. It was comprehensive. The study taught me that medical practice did not mean only to check the patient and offer medicine for administration. But it included so many things. It strengthened my belief in realizing the importance of public health and the importance of prevention.

After passing the examination, I started working in hospitals for practical knowledge and experience. I also joined the Tropical Medicine and Hygiene course in the University of Liverpool and received the Diploma in Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (D.T.M. & H.). Later I joined the University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne and took a course on Public Health. I was awarded the Diploma in Public Health (D.P.H.)

Return to Nepal

I came back to mid-1967 and was asked to join the Department of Health. There were very few specialists in public health. With degrees and experiences in pediatrics, public health, I was expecting to do something in public health. The Director-General of the Department insisted me stay in the Department as Assistant Director-General, heading planning and training division. Instead of moving to practice, I was assigned to look at the administration, planning and training in the ministry. I was interested in planning but administrative work was boring. The state of doctors working in remote parts of Nepal was pathetic and the opportunities available for higher education used to go for doctors living in Kathmandu. Those who are assigned outside Kathmandu or remote parts of Nepal often declined such an opportunity due to the Minister’s favor. I also developed criteria for further education abroad but the minister resisted, obviously, to send his own people. I resisted the issue saying that the priority needed to be given to doctors serving in remote parts of the country. Later on, I had differences with the minister regarding the selection of the candidates for higher education. I did not budge on taking the decision on the basis of merit.

Department To Bir

As differences grew I was transferred to Bir Hospital as deputy medical superintendent. I didn’t have the interest to go to Bir Hospital but I had to join the office. I told the minister that I had specialized in public health and as a pediatrician and I did not have a specialization in hospital administration. However, nobody listened to me. After serving one and a half years, I was finally transferred to Kanti Children Hospital which was built under the assistance of Russia. Actually, it was a general hospital but failed to lure patients due to distance. It was regarded as a faraway hospital. As it lies in the heart of Kathmandu, Bir Hospital used to be the choice of doctors and patients.

Bir To Kanti

After a low volume of patients in Kanti Hospital, the government turned it into a children’s hospital. We, all pediatricians, also lobbied for a specialized hospital. Then, it came to be the first child hospital. I was given an offer to go there which I accepted immediately.

Along with me, six doctors were posted there. They included Dr. Pushpa Lal Rajbhandari, Dr. Yogendra Bhakta Shrestha, Dr. Hemang Dixit, Dr.Manindra Ranjan Baral and Keshab Rajbhandari, a pediatric surgeon. It was a 50-bed hospital with only six doctors. We had divided 6 beds each for all of us, with a few common beds in an emergency. It used to be a remote hospital from Kathmandu and very few patients came there. I spent there with not enough work. I felt some frustration again. In the meantime, I was approached if I would be available to consult sick children in newly established SOS Children Village at Sano Thimi on a voluntary basis without remuneration. I agreed as I was not very interested in private practice and would visit the Village twice a week.

Family Planning Association

When I came after completing MBBS in 1958, the movement of family planning was gradually taking shape globally. It had also affected Nepal. India had started the Family Planning Association. One foreign lady from the Pathfinder Fund visited Nepal and advocated for starting the Family Planning Association in Nepal as well. She had approached social workers like Princess Princep Shah, Kamal Rana, Punyaprabha Devi Dhungana to constitute the association, but received a lukewarm response. They did not seem keen to constitute an association as such in a conservative society where nobody wanted to listen about family planning. As I had worked for a student clinic at Trichandra College, I used to have a lot of time. I was also active in the Nepal Medical Association as the Assistant Secretary. I was young and preferred to be active. The representatives of the fund approached me if doctors can help to set up such an organization. We had realized that family planning can be a strong tool to reduce the higher maternal mortality rate of Nepal. Nepal had between 1500-2000 per 100000 maternal mortality ratio. The infant mortality rate was 300 per thousand live birth. It was very high. Given the circumstances, the fund’s representative sounded reasonable. We set up a Family Planning Committee under the Nepal Medical Association and approached the social workers to take up leadership. Eventually, the Family Planning Association was established in 1959 with Dwarika Devi Chand Thakurani, first woman assistant health minister, as President at our request to take the lead because family planning was about women’s health. She agreed to our proposal. I was very active there before I left for England for further studies.

Journey to Prashuti Griha

When I was transferred to Kanti Children Hospital, I did not have much work. I was interested in clinical and fieldwork. At that time Prashuti Giriha was searching for some pediatrician to help them support the neo-natal ward for the newborn babies. They requested me to say that they didn’t have the money to pay. As I had more or less no work in Kanti Children’s Hospital, I found the offer was good. I agreed to work there as well. After working for a few months, I left for the United Kingdom again for further study. I took the training on neo-natal pediatrics for newborn babies. I worked there for 10 months and came back in 1972.

Prashuti Griha Again

After returning from the UK, I continued to serve in Prashuti Griha. It was the first hospital to set up the neonatal unit. This unit had saved many newborn babies at that time.

Many babies died due to jaundice and without treatment. I happened to be the first of doctors who successfully made exchange transfusion, as I knew the technology well. My first success story was the daughter of the Litterateur Gita Keshari. She had jaundice soon after birth and needed blood transfusion urgently. When we needed O Negative blood for transfusion, we were unable to find anyone with blood matching with that of the child. Finally, someone told me of a Nursing Officer in the World Health Organization have O-negative blood. Talking to her, she volunteered to come to the hospital in the middle of the night to donate her blood and the exchange transfusion was successfully done in the early hour of the morning and the baby girl’s life was saved. I used to think that I could save a few babies here but how about the rest. More and more I realized that curative medicine could save a few babies but the only preventive approach could make a big difference in saving the lives of hundreds.

Family Planning And Maternal Child Project

In 1968, Nepal Family Planning and Maternal Child Health Project were established as a semi-autonomous body with enough budget. While I was still working in Kanti Children Hospital, then Chief of the Project Dr. Yag Nath Sharma approached me asking if I can join the Project. He said that the U.S. government’s focus in Nepal was mainly in family planning and it was considered necessary to have a pediatrician to join the office to look after maternal-child health. I accepted the offer and joined the office as a senior pediatrician at the cost of sacrificing clinical work. Later I was promoted to deputy chief and I was appointed project chief in 1975.

During that time Nepal also started to give priority to the population. Interest in population had also increased. As international pressure grew, Nepal too started developing a population planning policy. In 1975, a separate entity, Population Policy Coordination Board was established within the National Planning Commission. It was a major change in the overall policy of Nepal. I was appointed as a member secretary of that board. Later this body was upgraded as National Commission on Population under the Chairmanship of Rt Hon’ble Prime Minister of Nepal. I continued as Member-Secretary of the Commission with the FP/MCH Project as the Secretariat until a separate Secretariat was established after a couple of years.

When I joined the project, the free distribution of condoms and pills had already started with US assistance. Even helicopters were chartered to distribute condoms in remote parts of Nepal that were merely a waste.

As we didn’t have the data, I realized that the stereotype of the western model to distribute the condoms and pills through establishing an office and visiting home was not enough. As a remote mountainous country, with traditional society and low-level literacy, Nepal required a different approach.

We started to build grassroots level networks by establishing Panchayat based health workers. Instead of appointing them from the center, the project also handled the recruitment of health workers from local bodies. We also decided not to make them paid staff. They were like volunteers. The work of such volunteers was to keep records, distribute pills and condoms and hold meetings and suggest women and children about maternity health. They were also given the responsibility to motivate women and men about the importance of condoms and pills. They were also given the role to disseminate the information regarding family planning camps and motivate people in favor of small families. Under MCH, they were trained to mix salt, sugar and water to use in preventing diarrhea. We used to provide Rs.100 a month for volunteer work. We provided basic training for them.

They started to collect information from the community. The concept used by the Family Planning/MCH Project worked as a foundation for today’s Female Community Health Workers (FCHWs). We had experimented with several models, including a team of husband and wife. Our effort was to make the health system community based rather than hospital-based. It was a bottom-up approach. During 1979, the literacy rate was low, unhygienic lifestyle pervaded the community level. Prevention alone could bring a lot of change. The work of Panchayat health workers was to build an information network. Their work was to distribute nutrition-related medicines like Vitamin D and Vitamin A capsules to children and iron tablets to pregnant women. In 1982, the New Era evaluated the role of Panchayat Health workers and recommended that though costly to start with it had great potential to be cost-effective and should be continued.

Family Community Volunteer Health Workers

Panchayat health worker was a foundation of FCVHW which started in 1986. Department of Health pursued the need to focus on public health. Although the United States of America had started recruiting the health workers at the grass-root level since the early 1950s to carry out Malaria eradication project activities, this was how the public health system started in Nepal. In a series of evolution, Nepal’s current level of community public health came to be in practice. There were all problems in the community. We asked it to recruit volunteers, preferably women.

The Family Planning/ Maternal Child Health Project conducted the first national fertility survey as part of the World Fertility Survey. This survey provided an opportunity to understand the demographic pattern in Nepal. It also generated awareness among the policymakers about the importance of data. After working in the project, what came to realize that Nepal needs a community-based health system. This knowledge was generated. Our project had immensely contributed to making our health system community based on the bottom-up approach..

Evolution of the Health Sector

It was tough to start responding to epidemics, of cholera, typhoid and jaundice, which used to kill a lot of people in the early days. When there were no official records, no curative medicines and preventive methods, many people would die. We built everything step by step, from scratch to the present level of units, of reporting system from the bottom of FCHV to Health Posts, District Hospitals, Regional Hospitals and Central Hospitals. Similarly, for prevention, district-level public health offices were established all over the country with effective monitoring and information system. However, what I see now is a certain level of destruction and confusion following the new political restructuring.

First Move in Fertility

FCHV started in 1986-1987. During the period, the Department of Health Services gave priority to the community based preventive health system. There were a separate worker and post for malaria, where people used to report their state and they administered medicines. They took the blood film and blood slide. Leprosy had also community health workers. All of them contributed to the development of integrated health services. The malaria control program had a budget for insecticide. However, Family Planning and Child Health are more related to human health in general and not limited to eliminate/eradiate one disease. The United States has been here since the early 1950s in the health sector. They have immensely contributed to developing health systems in Nepal, including the community health, as documented in The Four Decades of Development: The History of US Assistance To Nepal. It was also published twenty years later with the updated data. This is a book worth reading to learn about Nepal’s health system and the contribution of USAID in Nepal.

There used to be a rampant epidemic of cholera, malaria, typhoid, and measles, and so on. However, Nepal used to fight the battle without many curative and preventive strengths. It was like survival of the fittest. The situation is now different.

Contribution of Health Planning Division

I was later transferred to the Planning Division of Ministry of Health where I got a good opportunity to plan for health and implement it in 1983. All the information and data came to my division. Later on, we established a data bank. We also decided to start Health Management Information system. Even Department Health established a unit and started to collect the data and information. This helped us solidly to know the state of diseases in different parts of the country and types and its rate of infection. During my period in planning, a new concept of basic minimum needs had come up. This included health, food and shelter. Late King Birendra was very much interested in basic needs and the component of health was a high priority. As I worked in the planning, I could contribute my experience. I later joined the WHO where I looked after health planning and policy planning. In 1991, Nepal drafted First National Health Policy and I had contributed from WHO. First Long Term Health Plan was formulated in 1975. I was very much part of this and the Second Long Term Health Plan. Nepal has built good health infra-structures from grassroots upwards. At the community level, different groups like mothers and youths are involved and at the community level, there are health posts and top-level hospitals. Bihari Krishna Shrestha had played a major role to make FCHV operational and functional. I really enjoyed working with Bihariji, a person specializing in a rural community and of that background, in the Ministry of Health. His approach helped us to determine the way we needed to go. We had designed the health system around community health workers, health posts, district office (hospital), regional directorate Health Office, hospital and Department of Health Services and Ministry and Central Hospital. Hence, we developed a very good information system at the district level.

Keshab Poudel

Poudel is the editor of New Spotlight Magazine.

- FOURTH PROFESSOR Y.N. KHANAL LECTURE: Nepal-China Relations

- Jun 23, 2025

- Colonel JP CROSS: Centenary Birthday

- Jun 23, 2025

- REEEP-GREEN: Empowering Communities with MEP

- Jun 16, 2025

- BEEN: Retrofitted For Green

- May 28, 2025

- GGGI has been promoting green growth in Nepal for a decade: Dr. Malle Fofana

- May 21, 2025