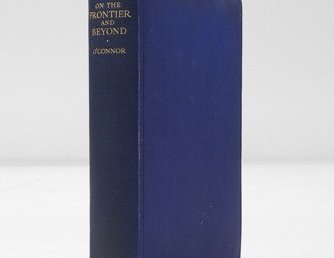

William Frederick Travers O'Connor, author of "On the Frontier and Beyond: A Record of Thirty Years' Service"(London: John Murray, 1931), was an English civil servant with substantial exposure of the British Indian frontier region including Nepal.

O'Connor lived in India for seven years between 1895 and 1902 travelling from Darjeeling, which once formed the part of Nepal to the North-West Frontier Province, to the Gilgit District in the State of Kashmir. He spent further twenty-three years in Tibet, Persia and Nepal. He accompanied Colonel Francis Younghusband’s expedition [1903-04] as secretary and interpreter and remained in Gyantse, the third largest town in Tibet at that time,as British trade agent after being wounded. After visiting and spending about three years in Persia and a few months in Serbia in 1918, O’Connor got an opportunity to be transferred to Nepal as a British resident in 1918-20.

The Segauli Treaty between Britain and Nepal was signed two years prior to his arrival. Subsequently, he served in Nepal as a British envoy during 1921-1925. In his new capacity, he also received visiting Prince of Wales in Nepal in his sport mission. In 1923, when an Anglo-Nepalese Friendship Treaty was signed by Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher, whom he described as “the late Prime Minister of that gallant and friendly little country,” he represented and signed for British side. The book includes his personal experiences in all these places, the text of the said treaty and the record of the British royal shoot in Nepal in 1921 as well as the summary of big game shot in Nepal in four seasons.

In the author's opinion, the objective of the book “is merely to try to give an idea of the scope and interest of the work which devolves on the Officers of [his] Department on and beyond the frontiers of India.” To a Nepalese reader, the book has important historical references about Nepal, whose capital is only 75 miles from rail-head, and “was in some respects the most secluded and isolated of all the above places.” He further describes Nepal as “a hermit kingdom” jealously guarded and preserved.

O'Connor makes it clear in his book that the system of government in Nepal is led by prime minister. Although, by this time the expression ‘His Majesty’ was already in use for the King in Nepal, his role in governance was only ceremonial. His status is compared by the author with the status of the historical ruler in Japan, “where a figurehead Emperor was maintained in imperial state and seclusion, whilst the Prime Minister, in the shape of the Shogun [the hereditary military governor], actually ruled the country.” In the same vain, the king of Nepal was treated with “great ceremonial respect, and surrounded by every symbol of royalty magnificent palaces, jewels, attendants, etc - but actually, in practice, he is the merest figure-head, and all power resides in the hands of the Prime Minister, the Maharaja.”

He further adds that the Prime Minister “is assisted by a Council composed of all the Chief Officers of the State, civil and military, which meets daily, and with which the Prime Minister discusses affairs of State. But its functions are purely advisory; and although the opinions of the members of the Council are valued and weighed, and their votes taken on occasion, the Prime Minister in all cases remains the sole executive and administrative authority.”

While O’connor clearly mentions about the dictatorial regime at work in Nepal, he has high appreciation for both the country and Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher, who received the same level of appreciation from Perceval Landon, in his famous book “Nepal” in 1928. According to O'conner, Chandra Shamsher “was a man of striking appearance, courteous and dignified in manner, but alert, forceful, and brimful of intelligence and interest.” According to him, the English speaking prime minister knew every detail of the administration. His knowledge of foreign affairs and the British Empire is much appreciated in the book. One exemplary sentence of O’Connor states: “He was, in a word, at once a diplomat, a man of affairs, and a natural born ruler and leader of men.”

The immense goodwill about Nepal can be read everywhere in the chapters that O’Connor has devoted to Nepal. He writes: “[Nepal] is not, as is so often believed, one of the feudatory States of the [British] Indian Empire, but is an entirely independent Kingdom with its own Monarch, army, system of government, etc.” It has “a sane and well-considered foreign policy” which maintains “Nepal's rights and sovereign integrity as an independent country.” Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher “carefully avoided friction with his neighbours, and steadily fostered and cemented Nepal's traditional friendship with Great Britain.” The author remembers meeting Chandra Shamsher at King Edward VII's garden-party at Windsor Castle in July 1906.

O’Connor has explained how the treaty of 1923 was negotiated between Nepal and Britain and finally signed. Though the Treaty of Segauli signed between the two countries to conclude the Anglo-Nepal War in 2014-16 had served its purpose very well for a long period, the Nepalese side did not want any possibility of misinterpretation its provisions de-recognising “clearly and unequivocally the complete independence of Nepal.” He states: “This latter point was, indeed, one to which the Prime Minister and all Nepalese subjects attached the very highest importance. Although, no doubt, Nepal's status as a sovereign state was implicit in the Treaty of Segauli, and although her independence had never actually been called in question or challenged, certain incidents had occurred in the past (which need not be particularised here) which had given cause for some anxiety on the part of the Nepalese Government, and there still existed a good deal of public misapprehension regarding the true status of the country.”

It is clear that some critics thought of Nepal as one of the "native states" of British India, and the existence of the Gurkha troops in the Indian army “tended to foster this impression.” So adds the author: “It was therefore desirable to dispel any such mistaken idea once and for all, and to place the true position of affairs beyond a doubt.”

The book also acknowledges the Nepalese military and highlights financial and various other assistance provided by Nepal to British India in its difficult times. Referring to the First World War, the author says: “Nepal lay under no obligation, either contractual or moral; to come to the assistance of Great Britain in her time of trouble; but the Prime Minister did not hesitate for a moment. The friendship which had for so long existed between the two countries represented to him something more than a mere sentiment.” The tradition of providing support to the British that Prime Minister Jung Bahadur Kuwar [1816-1877] started at the time of the Indian Mutiny in 1857 continued with no expectation for guarantees or pledges or reward. But the British refunded a part of the Terai that that they had confiscated in the war following the suppression of the Mutiny.

Almost five and half decades later, in recognition of Nepal’s services during the First World War, similar gesture was expected by Nepal. In fact, Nepal wanted the rest of the Terai stretches confiscated during the war to be given back to it by the British. But this time the British government thought it was not so easy: “At the time of the Mutiny the districts in question lay mostly in the territory of rebellious Chiefs or Rajahs, and had not been included in the land settlement of British India proper, and their transference to Nepal had presented no particular difficulty and had involved no breach of faith with the inhabitants.”

The situation now was different. Because “since 1858 the whole of the border districts had been subject to a regular land settlement, and the Government of India could not very well agree to transfer to another country districts which, for over half a century, had formed an integral part of British India, without the consent of the population and of the other interested parties.” The matter was discussed by O’Connor with Prime Minister Chandra Shamsher, and later the British provided monetary support to Nepal, rather than giving back its earlier Terai territory. These discussions took place in 1919.

The book, authored by O’Connor, has a great deal of interesting details for modern minded Nepalis. At one instance, the author maintains that “the most usual form of social entertainment, for instance, namely, that of eating and drinking together, was utterly " taboo," [in Nepal] as none of our high caste friends could partake of our food or drink, or invite us to share theirs.” At another instance, he states: “Katmandu, in spite of its secluded situation and apparent inaccessibility, possesses a number of really magnificent palaces and halls of audience.” The author quips that Chandra Shamsher humorously likened Singh Durbar, his residence, as "No.10 Downing Street" of the British Prime Minister.

Talking about the excellent library of General Kaiser Shamsher, O’Connor speaks his heart when he says: “It was really rather surprising, in this remote and almost inaccessible mountain Capital, to find oneself in a thoroughly up-to-date library, which comprised not only the more usual works of reference, history, biography, etc., but also a selection of the latest works of fiction, all supervised by a host who was himself an omnivorous reader and who thoroughly appreciated what he read.”

Obviously, the Ranas of Nepal who are remembered in history for their undemocratic form of government had in fact many good things to their credit that the present generation of the Nepalese could be appreciative of.

Dr. Bipin Adhikari

Dr Adhikari is a senior constitutional expert and the founding dean of the Kathmandu University School of Law). He can be reached at [lawyers_inc_nepal@yahoo.com]

- Belt And Road: No Belt, No Road – The Stalled Journey In Nepal

- Oct 26, 2023

- On The Belt And Road Cooperation And Partnership 'Model Agreement'

- Oct 17, 2023

- Mobilizing Resources For The University Of Nepal

- Jul 06, 2021

- Insight Into The Political Economy Of Nepal’s Development

- May 27, 2021

- Preliminary Part Of Padma Shamsher's Government Of Nepal Act, 1948

- May 04, 2020